NEXT STORY

Gandhi and Nandalal Bose

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Gandhi and Nandalal Bose

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11. Travelling to Santiniketan and being searched by the police | 62 | 02:20 | |

| 12. Life at Santiniketan and Nandalal Bose | 121 | 03:36 | |

| 13. Santiniketan and Gandhism | 59 | 05:12 | |

| 14. Mohandas Gandhi and art (Part 1) | 67 | 06:54 | |

| 15. Mohandas Gandhi and art (Part 2) | 57 | 06:52 | |

| 16. Gandhi and Nandalal Bose | 74 | 07:30 | |

| 17. Tagore | 64 | 04:47 | |

| 18. Art and religion | 64 | 06:58 | |

| 19. Benode Behari Mukherjee, Brahma and Tulsidas’ monkey god | 84 | 04:47 | |

| 20. Developing relationships with Benode Bihari Mukherjee and... | 60 | 03:14 |

So Nandalal says, ‘Look, I have no experience in these matters - I’m, just a painter’. So then it seems he sort of writes to him a sort of a small note saying, ‘You see, I do not want a trained violinist, I want a fiddler’. So Nandalal says it sounded so pressing, so he went there, he sat with people and to a certain extent what they did in the Faizpur Congress with just local materials, straw and bamboo and matting and things of that kind, became more or less a sort of a brand idea for all subsequent public designers in India. I mean even when Dashrath Patel did something for the Paris Festival of India, it was more or less based on that old idea. But anyway he did that, but there is no record of that. There is no photographic record of that. And after that, because Gandhi then said, ‘I will take you from sort of place to place and show you what Nandalal has done’. And Nandalal, who was till then known only within the four corners of Bengal, became a national figure. And in fact, Nandalal was extremely, I think being a shy man, extremely embarrassed about such notice. There is a story which I suppose is not apocryphal, because at that time Nandalal’s work group had a very handsome young sort of Punjabi, young man, in the group who had gone to help. I came to know him later in the day when I was becoming a professional here in Delhi. His name was Jaipal Mehta. So he was there in that group. And it seems people used, after hearing Gandhi’s voice, all the visitors to the Congress used to come to see who is this Nandalal, we want to see. So Nandalal, it seems, asked Jaipal, he said, ‘You do me a service. You lie on this cot here, this sort of a thing, and do me this service’. So whenever people used to come and look for Nandalal, Nandalal used to quietly point out to them, ‘That is Nandalal’. So it seems people used to say, ‘Oh, he’s so good looking and his work is also so good’. Now the whole question is this may be just a story, but this is very typical of Nandalal. He always used to be sort of withdrawing. But this is the time when well Nandalal got more involved and when the next Congress came to be in Haripura in Gujarat he was again called. Then by that time Nandalal, I understand, had already heard that there was some grumbling that Gandhi was depending on a Bengali artist too much and there are artists elsewhere. So later I think Gandhi had [unclear] on to in a certain, he’s a sort of secretary, Mahadev Desai had also written about this question in the Bombay Chronicle, I have heard. I had seen that article somewhere but I haven’t been able to locate it. Well, they were trying to say no, everyone will have work but let Nandalal do something that he can do best. And that is how the about a hundred and odd Haripura posters came into being. And Nandalal at that time camped here and then sketched, and there are lots of sketches he has done of the rural life here. But what I am saying is there were differences, there were, and Nandalal had written a later article and he says that he had had a chance to sort of talk with Gandhi at that time. He had heard that probably some of the enthusiastic Gandhites, especially in the [unclear] public, they wanted all the Khajuraho sculptures, which they thought were sort of highly erotic and should be covered up. And also similarly in Konarak, so it seemed Gandhi was asked by Nandalal saying, ‘Is that true, and then will you allow it?’ He said, ‘No, it will never happen’. At the same time he got a little more enthusiastic and said, ‘Bapu’, he used to mention to him as Bapu, ‘haven’t we had enough of temples? Shouldn’t we sort of where people go in for hospitals and all this kind of thing?’ And Gandhi is supposed to have said, and Nandalal himself quotes that, ‘Well if people want to visualise the All Powerful Being and then worship Him, who can stop?’ So this kind of a thing is there. There is, and later when the ashramites of the Gandhian institutions wanted to have a cultural sort of a grounding, they went to Santiniketan. And when the Santiniketan people wanted to have an exposure to the realities of life, they went to Sevagram and this has been going on. In fact Sushila is one of them, my wife, because she was selected by, then Gandhi was still alive, when the Kasturba Memorial Trust came into being, and the first Chairman was Sucheta Kripalani who was very close to Gandhi at one time, that [unclear] and his wife. She had at one time taught Sushila in the College, history. And later she knew that Sushila had spent a year here in Santiniketan at the same time as Satyajit Ray [unclear] and these people. So...

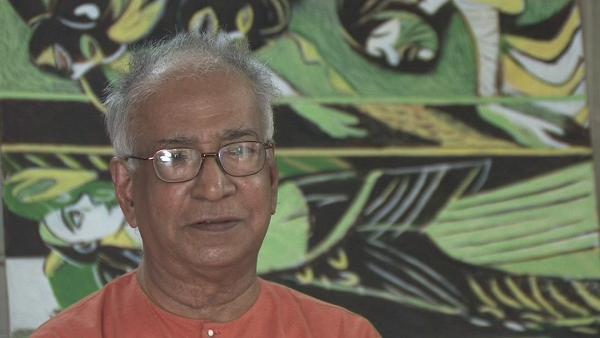

KG Subramanyan (1924-2016) was an Indian artist. A graduate of the renowned art college of Kala Bhavana in Santiniketan, Subramanyan was both a theoretician and an art historian whose writings formed the basis for the study of contemporary Indian art. His own work, which broke down the barrier between artist and artisan, was executed in a wide range of media and drew upon myth and tradition for its inspiration.

Title: Mohandas Gandhi and art (Part 2)

Listeners: Timothy Hyman

Timothy Hyman is a graduate of Slade School of Fine Art, London, in which he has also taught. In 1980 and 1982, he was Visiting Professor in Baroda, India. Timothy Hyman has curated many significant art exhibitions and has published articles and monographs on both European and Indian artists.

Duration: 6 minutes, 53 seconds

Date story recorded: 2008

Date story went live: 10 September 2010