NEXT STORY

The role of the film director in today's Poland

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

The role of the film director in today's Poland

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 181. Conversation with Akira Kurosawa about Shakespeare | 272 | 03:02 | |

| 182. The role of the film director in today's Poland | 41 | 02:51 | |

| 183. Revenge - a film about Poles | 49 | 03:30 | |

| 184. Roman Polański in Revenge | 99 | 01:40 | |

| 185. A short history of Poland before the 19th century | 62 | 04:15 | |

| 186. A short history of Poland since the 19th century | 43 | 02:39 | |

| 187. Katyń | 68 | 05:30 | |

| 188. The new politics after 1989 | 56 | 02:28 | |

| 189. Senator Andrzej Wajda | 32 | 03:09 | |

| 190. Politician - film director | 27 | 05:41 |

What did I believe in when I was starting out making films? I was simultaneously influenced by the films of Bergman, Fellini, Kurosawa, great masters who knew how to make films that we could all watch, the whole of Europe. I had a conversation once with Kurosawa, as it had always fascinated me to learn from him how he had managed to fathom Shakespeare so brilliantly in his film, Macbeth, which in Poland had been renamed as The Bloodied Throne. It's not just a fantastic film but it also had additional fragments which aren't there in the original but which Shakespeare ought to have written himself. I wondered to myself how it was possible for a Japanese film director to have come so close to Shakespeare. I had the good fortune to meet my master and teacher, Akira Kurosawa, in his home where he'd invited me. I put this question to him and his reply astonished me. Looking at me, he said, 'But you know that I took my high school graduation exams in Tokyo.' I was intrigued by what he wanted to say to me by this. What he wanted to say by this was that the world at that time was made up of people who had passed the same exam and so had a common language. Anyone who had passed this exam knew who Shakespeare was and understood what he was saying whether to a Japanese person, Chinese or anyone else. Fellini in Rome had passed this exam, as had Bergman in Stockholm, and I was the only one who hadn't but I had made up for this deficiency. I understood European literature which is why he was... well, it was obvious, he said, 'I understand Shakespeare because I've passed my exams'. I think there was one other even more important thing: that audience which came to watch the films made by Bergman, Fellini, Kurosawa or Antonioni, they'd also passed their high school graduation exams. Because of this, there was a kind of understanding. It was an audience that watched these kinds of films. However, this audience suddenly disappeared, something ceased to exist. This audience wasn't interested, didn't feel an obligation to find out who Adam Mickiewicz was, what sort of situation I was trying to show in my film. If I'd made this kind of film 30, 40 years ago, it would have provoked interest in Europe, and because of the Berlin Wall, people would have wanted to learn something. Things are different today, if I don't understand something, if it isn't obvious then why should I watch it, what's it got to do with me?

W co wierzyłem tuż, kiedy zaczynałem ja robić filmy? Równocześnie wypłynęły filmy Bergmana, pojawiły się filmy Felliniego, pojawiły się filmy Kurosawy, wielkich mistrzów, którzy potrafili zrobić film, który wszyscy mogliśmy oglądać, cała Europa. Ja kiedyś miałem rozmowę z Kurosawą i ponieważ mnie zawsze interesowało, żeby on mi odpowiedział na pytanie: 'Jak to się stało, że on tak wspaniale przeniknął Szekspira robiąc swój film Makbet, który się nazywał w Polsce Tron we krwi, i który jest nie tylko fantastycznym dziełem filmowym, ale jeszcze w dodatku ma dopisane fragmenty, których nie ma u Szekspira i które właściwie Szekspir powinien był napisać?' Myślę sobie, jak to jest możliwe, japoński reżyser, jak on mógł się tak zbliżyć do Szekspira? No i miałem szczęście spotkać mojego mistrza i nauczyciela Akira Kurosawę w jego domu, zaprosił mnie. Zadałem mu to pytanie i odpowiedź jego była zupełnie zdumiewająca. On mówi... patrząc na mnie, mówi: 'Ale Pan wie o tym, że ja zrobiłem maturę w Tokio?' Zaciekawiło mnie, co mi chciał przez to powiedzieć. On mi chciał przez to powiedzieć, że ten świat tamtego czasu składał się z ludzi, którzy mają maturę i mogą się pomiędzy sobą porozumieć. Ten kto miał maturę, wiedział kto to jest Szekspir i rozumiał, co Szekspir pisze czy do Japończyka, czy do Chińczyka, czy do innych. Taką samą maturę miał Fellini w Rzymie, taką samą maturę miał Bergman w Sztokholmie, tylko ja nie miałem matury, no ale nadrobiłem, że tak powiem, swoje straty i ja rozumiałem europejską literaturę. I dlatego on był... mówi: 'No to jest oczywiste, rozumiem Szekspira, bo mam maturę'. I myślę, że było jeszcze coś ważniejszego – ci widzowie, którzy przychodzili wtedy oglądać filmy Bergmana, Felliniego, Kurosawy, Antonioniego – oni też mieli matury. W związku z tym istniało jakieś porozumienie. To była widownia właśnie tego rodzaju kina. No ale ta widownia nagle gdzieś wyginęła, gdzieś właśnie coś się urwało. Ta widownia nie jest zainteresowana, nie czuje się zobowiązana, żeby dowiedzieć się, kto to jest Adam Mickiewicz, jaka to jest sytuacja, którą ja chcę pokazać w moim filmie. Trzydzieści, czterdzieści lat temu, gdybym zrobił taki film, on by wzbudził zainteresowanie w Europie. I z powodu muru berlińskiego, ale ludzie chcieliby się czegoś dowiedzieć. Dzisiaj nie – jeżeli ja tego nie rozumiem, jeżeli to nie jest oczywiste, to dlaczego ja to mam oglądać, co mnie to obchodzi?

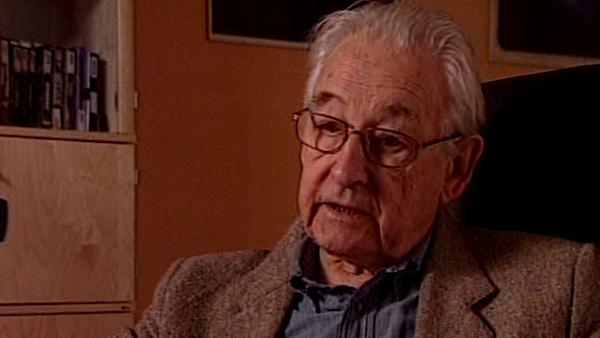

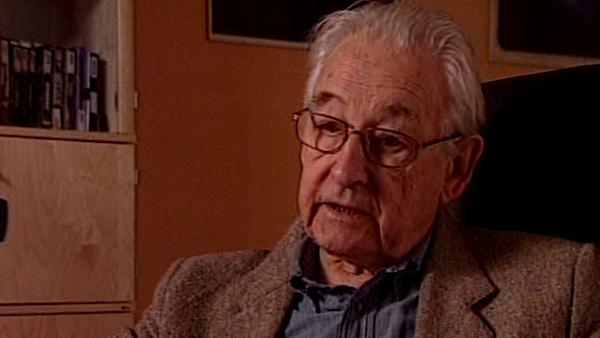

Polish film director Andrzej Wajda (1926-2016) was a towering presence in Polish cinema for six decades. His films, showing the horror of the German occupation of Poland, won awards at Cannes and established his reputation as both story-teller and commentator on Poland's turbulent history. As well as his impressive career in TV and film, he also served on the national Senate from 1989-91.

Title: Conversation with Akira Kurosawa about Shakespeare

Listeners: Jacek Petrycki

Cinematographer Jacek Petrycki was born in Poznań, Poland in 1948. He has worked extensively in Poland and throughout the world. His credits include, for Agniezka Holland, Provincial Actors (1979), Europe, Europe (1990), Shot in the Heart (2001) and Julie Walking Home (2002), for Krysztof Kieslowski numerous short films including Camera Buff (1980) and No End (1985). Other credits include Journey to the Sun (1998), directed by Jesim Ustaoglu, which won the Golden Camera 300 award at the International Film Camera Festival, Shooters (2000) and The Valley (1999), both directed by Dan Reed, Unforgiving (1993) and Betrayed (1995) by Clive Gordon both of which won the BAFTA for best factual photography. Jacek Petrycki is also a teacher and a filmmaker.

Tags: Macbeth, Bloodied Throne, Tokyo, Rome, Stockholm, Berlin Wall, Akira Kurosawa, William Shakespeare, Ingmar Bergman, Federico Fellini, Antonioni Michelangelo, Adam Mickiewicz

Duration: 3 minutes, 2 seconds

Date story recorded: August 2003

Date story went live: 24 January 2008