NEXT STORY

The mysteries of developmental biology and evolution

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

The mysteries of developmental biology and evolution

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11. 'Knowing' in science | 2 | 1675 | 01:58 |

| 12. How scientists and non-scientists perceive the world | 4 | 1830 | 02:39 |

| 13. What we don't know | 1 | 1557 | 01:08 |

| 14. Has science stripped the world of wonder? | 1 | 1408 | 03:39 |

| 15. The mysteries of developmental biology and evolution | 1483 | 01:37 | |

| 16. Our understanding of evolution | 1573 | 02:21 | |

| 17. Making predictions in science | 1083 | 01:08 | |

| 18. Understanding the brain | 1253 | 01:48 | |

| 19. Understanding the brain through reverse engineering | 1031 | 02:25 | |

| 20. Darwin's big idea | 1213 | 00:37 |

Well, I think it’s stripped the world of the wonder that people had in the past, but it’s replaced with a new sort of wonder in my view: this wonder of the very small and the very great and the very short and the very long, and all the strange objects and behaviours you find in between. Now one of the reasons I think that people think it’s inhuman, which is the other thing they say, is the most highly developed sciences at the moment are not the ones which are closest to us as people. They’re… they’re physics and chemistry. Chemistry in particular seems to have got a very bad name among people. To say something is chemical is a terrible thing to say, apparently, although they’re made of chemicals. It’s a bizarre… when you think about it. So, when… biology, since the… the introduction of molecular biology has also become a hard science but it still hasn’t got up to the brain and our feelings and our perceptions and things of that sort,and these are still in a half scientific world where we don’t have the insights and the explanations. Consequently, when people learn modern science it appears rather detached from the things that they, as persons, are mainly interested in. But that isn’t… that isn’t going to last. Another one or two hundred years we shall understand people’s behaviours and what it is that makes them think in this way and feel in this sort of way and so on, rather than the rather crude rules of thumb we have at the moment. Because obviously we do have rules of thumb, otherwise we couldn’t interact as social beings, but they’re not necessarily the accurate ones. That… there… it’s just… just the same in physics, there’s a physics… a sort of physics called Aristotelian physics after Aristotle, that’s what the ordinary person believes in physics. If you ask them questions, they… they answer as if it was Aristotle answering; they don’t answer as if it’s Newtonian physics. I mean, people do experiments on this… even with science… science… starting undergraduates often get the things wrong, you see.

[Q] What would be an example of that?

Well, the answer is, if… if you were flying along and you dropped a heavy bomb from an aeroplane and so on, where would the aeroplane be when the bomb hit the ground? Well, the… the correct answer is… most people think you leave the bomb behind, you see, well you do a little bit because of the friction of the air, but leaving aside the friction of the air, the fact is the bomb hits the ground immediately… underneath the aeroplane, you see. And that would be one of the standard… one of the questions they ask people and there are a lot of a number of similar ones and so on. So, people have rough and ready ways of dealing with people, you know, they think he’s angry, or he believes so and so, or this, that and the other, and that's… you can’t operate in society unless you have those beliefs. It isn’t clear that that’s going to be the way we should talk about it in another 100 years time, we shall still have to explain the behaviour, but we may interpret it in a… in a somewhat different way. Well, just as people in the past, sort of, thought that when there was a plague or something like that, it was a visitation from God and what was wrong was that they… they’d been sinning and they… and they had to pray for forgiveness of their sins so that the plague would go away. They didn’t have the concept of a bacterial infection. Now, the plague doesn’t go away because you think of it a bacterial infection, it’s just the way you look at it and the way that you behave. If you all congregate together in a church to pray that doesn’t necessarily a good thing because it may spread the plague, for example. If you knew about the… it being an infection and so on, then you would probably not do that. So, it does lead to different behaviour. But it doesn’t mean the actual phenomenon disappears because you explain it in a different way.

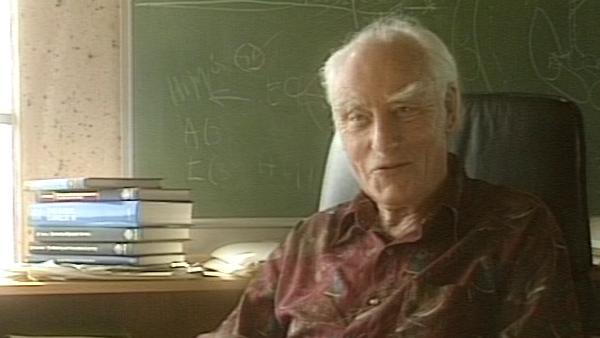

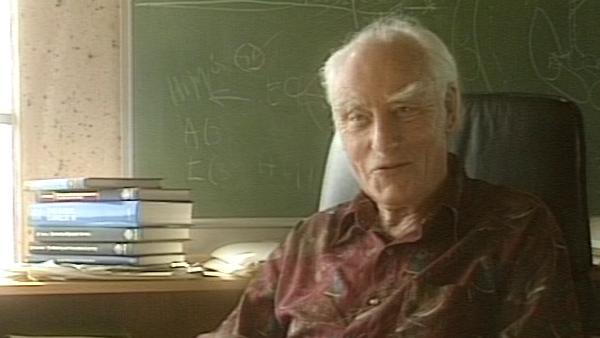

The late Francis Crick, one of Britain's most famous scientists, won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1962. He is best known for his discovery, jointly with James Watson and Maurice Wilkins, of the double helix structure of DNA, though he also made important contributions in understanding the genetic code and was exploring the basis of consciousness in the years leading up to his death in 2004.

Title: Has science stripped the world of wonder?

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is an independent documentary producer who has made a number of films about science and scientists for BBC TV, Channel Four, and PBS.

Tags: Isaac Newton, Aristotle

Duration: 3 minutes, 39 seconds

Date story recorded: 1993

Date story went live: 24 January 2008