NEXT STORY

Averill Liebow and the best compliment I've ever had

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Averill Liebow and the best compliment I've ever had

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 41. The philosophy of surgery | 261 | 04:24 | |

| 42. Judgement as the ultimate tool of a physician | 206 | 04:01 | |

| 43. The art of keeping yourself calm | 1 | 260 | 05:12 |

| 44. Surgery is fun! | 200 | 04:09 | |

| 45. Devouring medical literature | 186 | 03:54 | |

| 46. Averill Liebow and the best compliment I've ever had | 246 | 05:37 | |

| 47. The difference between information, knowledge and wisdom | 241 | 04:45 | |

| 48. The importance of being curious | 203 | 04:44 | |

| 49. 'Be kind, for everyone you meet is fighting a great battle' | 1 | 269 | 03:22 |

| 50. Percy Shelley's moral imagination | 207 | 04:34 |

Interestingly, this career that I love, or I should say my love for this career, I began to notice when I was in my late 50s, was waning the least little bit. And it was waning because I'd always been interested in the history of medicine, ever since I started medical school. And I was starting to write these essays on great figures in medical history and devoting more and more time to them. And recognizing… well, the only way I can put it is how poorly educated I was. I had, I thought, a very good college education. My degree was a Bachelor of Arts, it wasn't a Bachelor of Science. I had developed certain great interests in English Literature, for example. A particular course on the history of the English Bible had influenced me a great deal, and I had become a tiny bit of a student of religions, but as I studied more and more medical history, it became pretty clear I didn't really know a lot about Western culture or Western civilization. And the more I studied it, the more articles I wrote, the more articles I had to research, the more I recognized that the medicine of any era, of any age, is really an outgrowth of the culture of that age, of what the Germans call the Weltanschauungen, the worldly view of the people who lived at that time. And so certain kinds of changes occurred during the Renaissance. Another kind of change occurred during the Enlightenment.

Medicine was turned upside-down by the fresh winds of the cultural revolution, as a matter of fact. The attempts at democratization of Europe that occurred in the 19th century, specifically the revolutions of 1848, but there were others, and I became avaricious to learn about these things. And avaricious is the only term that I can think of. Every chance I got, I would find myself reading and I would find myself reading less and less of the surgical literature, because I have 24 hours in a day and I've got a surgical load, so what gets sacrificed is reading the journals. I've never been overwhelmed by the value of surgical journals anyway, you know. Even when I read them a lot, I would look through them for articles I thought were important to me, or helpful. And then I would quickly read them. I'd read the synopsis first, and then I'd see what I needed to read. We were so good at teaching one another, because there were so many conferences during the week. We have a Death and Morbidity conference, we have an X-Ray conference, we have other conferences where people tell their most interesting cases. We have other conferences where surgical research is talked about. We have other conferences where visiting dignitaries talk. So you really learned on the job, and journals, I didn't think, were really as necessary as the other aspects, except if you wanted to be very lordly and quote them. That was what the internists were very good at: always quoting literature and spouting it. That's how you impress people.

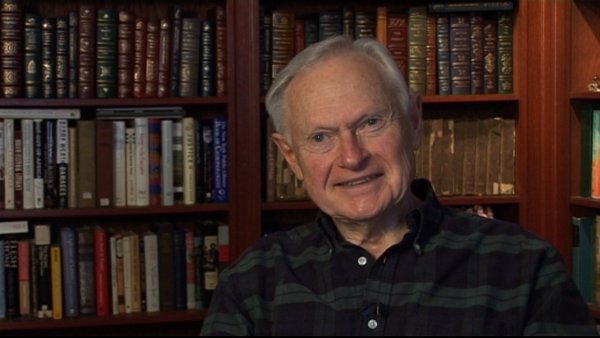

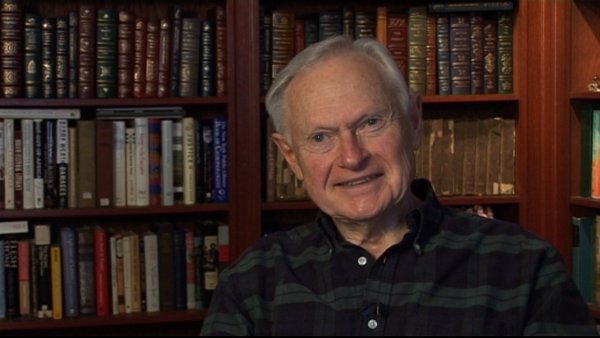

Sherwin Nuland (1930-2014) was an American surgeon and author who taught bioethics, the history of medicine, and medicine at the Yale University School of Medicine. He wrote the book How We Die which made The New York Times bestseller list and won the National Book Award. He also wrote about his own painful coming of age as a son of immigrants in Lost in America: A Journey with My Father. He used to write for The New Yorker, The New York Times, Time, and the New York Review of Books.

Title: Devouring medical literature

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is a London-based television producer and director who has made a number of documentary films for BBC TV, Channel 4 and PBS.

Tags: Bible, Europe

Duration: 3 minutes, 54 seconds

Date story recorded: January 2011

Date story went live: 04 November 2011