NEXT STORY

Why I'm grateful to Adolf Hitler

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Why I'm grateful to Adolf Hitler

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Canoodling among the carpets in my grandfather’s shop | 191 | 03:38 | |

| 2. My secret romance | 123 | 02:14 | |

| 3. Born in a shower of tears | 86 | 01:55 | |

| 4. Discovering some of the world’s wonders | 83 | 05:34 | |

| 5. How I came to possess 'mysterious powers' at school | 85 | 05:24 | |

| 6. School survival strategies | 71 | 04:13 | |

| 7. Why I'm grateful to Adolf Hitler | 1 | 143 | 03:43 |

| 8. Barnstable – our haven from Hitler | 69 | 06:02 | |

| 9. The end of childhood | 64 | 03:45 | |

| 10. My friend Eddie Breeze | 58 | 01:51 |

I was so upset, emotionally, that at night, I pissed my bed, every night, regularly. I pissed my bed. I couldn't stop it. But in order that the boys should not despise me for that infantile habit, I had the habit, after lights were out in that dormitory, of telling them a story. A story of ghosts, criminals, all kinds of horror, so that when one of the boys would scream, 'Shut up, Aldiss, you bastard!' that was my triumph, as they scudded down the bedclothes to hide themselves. Now, isn't that very peculiar? You see the whole shaping of the man – perhaps everyone's like that – but in my… in my extreme, I do remember it all, and I'm not making it up, that's the way it was.

And I then started to lecture to the boys after school, and I would lecture to them about the prehistoric world. And the boys would sometimes take notes. As for the microscope, the boys were all keen to look into it and see what they could see. And so, there were various things we could put under the microscope, including a hair from the head of a boy called Mickey. And when we put it under the microscope, we saw there was something living on it. This was death to Mickey... I can't tell you... oh God, he's got these creatures in his hair!

But all these things... and occasionally, Humphrey Fenn or his master under him, a chap called Knowles, would take us down through this forbidden gate and make us swim in the grey North Sea. And that was okay... that was okay. I suppose we liked it. It was a change, at least. And also, inside that gate there was the making of a garden, and so we could have a strip. And, of course, we were ill-fed, and so we devised the idea that if, towards the end of the January term, we planted certain vegetables seeds, when we came back for the next term, the summer term, these things would be growing up and we would have vegetables we could eat – radishes, lettuces, I don't know what else, but… it did teach us something.

Oh dear, those three years with Humphrey Fenn... quite extraordinary. Long after that, I went back to see that place. It had now become a boarding school, and it was actually run by Humphrey Fenn's son who was a kind of a squalid fellow, I thought. But such is fate. And that whole coast, which at the time I thought was most romantic, has deteriorated. I don't know. One becomes more critical, I suppose.

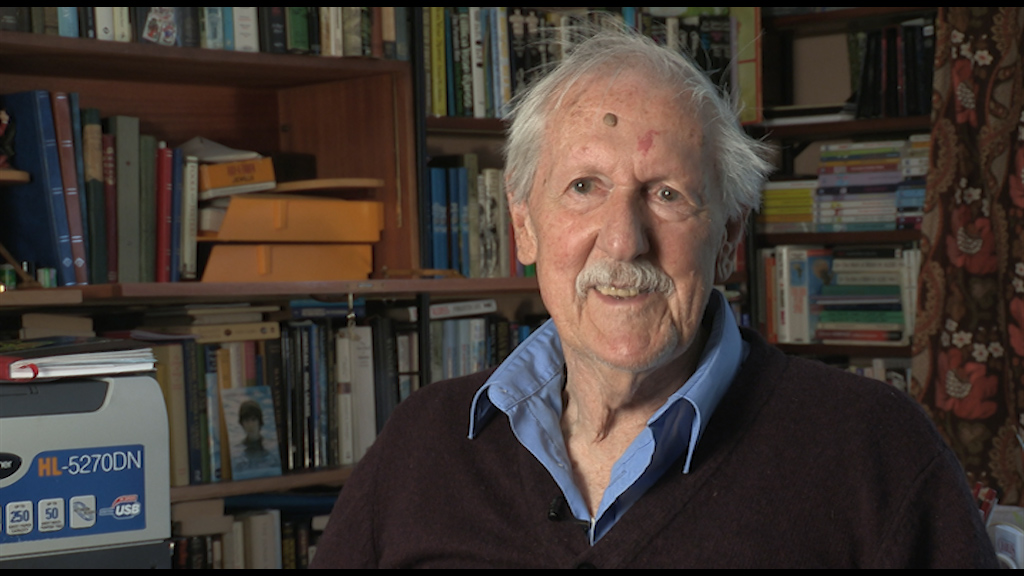

Brian Aldiss (1925-2017) was an English writer and anthologies editor, best known for his science fiction novels and short stories. He was educated at Framlingham College, Suffolk, and West Buckland School, Devon, and served in the Royal Signals between 1943-1947. After leaving the army, Aldiss worked as a bookseller in Oxford, an experience which provided the setting for his first book, 'The Brightfount Diaries' (1955). His first science fiction novel, 'Non-Stop', was published in 1958 while he was working as literary editor of the 'Oxford Mail'. His many prize-winning science fiction titles include 'Hothouse' (1962), which won the Hugo Award, 'The Saliva Tree' (1966), which was awarded the Nebula, and 'Helliconia Spring' (1982), which won both the British Science Fiction Association Award and the John W Campbell Memorial Award. Several of his books have been adapted for the cinema. His story, 'Supertoys Last All Summer Long', was adapted and released as the film 'AI' in 2001. His book 'Jocasta' (2005), is a reworking of Sophocles' classic Theban plays, 'Oedipus Rex' and 'Antigone'.

Title: School survival strategies

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is an independent documentary producer who has made a number of films about science and scientists for BBC TV, Channel Four, and PBS.

Tags: story-telling, microscope, swimming, vegetables

Duration: 4 minutes, 13 seconds

Date story recorded: September 2014

Date story went live: 17 August 2015