NEXT STORY

Butter barrels and sauerkraut

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Butter barrels and sauerkraut

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11. School of Fine Arts in Kraków was my destiny | 115 | 03:17 | |

| 12. Our awareness of the war | 135 | 05:08 | |

| 13. Butter barrels and sauerkraut | 95 | 01:19 | |

| 14. Polish reality at the end of the war | 142 | 01:49 | |

| 15. Sudden need for horse bits signals end of war | 128 | 02:13 | |

| 16. Road leading to School of Fine Arts | 118 | 05:10 | |

| 17. Out with the old, in with the new | 79 | 05:29 | |

| 18. Student self-teaching group leads to friction | 67 | 04:19 | |

| 19. School of Fine Arts - my participation in student life | 64 | 05:08 | |

| 20. Am I a painter? I'm a film director | 118 | 02:45 |

Jeszcze na chwilę warto wrócić do tego, jak nasza świadomość tego, co się wydarza, była niewielka, dlatego że to bardzo dużo tłumaczy z zachowania ludzi w czasie okupacji. 17 września w ogóle był poza nasza świadomością, dlatego że my uciekliśmy z matką, jak opowiadałem, do małej wioski koło Kazimierza nad Wisłą. Chaos i całkowity brak orientacji polskiej armii, to co się wydarzyło, ten cios był też strasznym ciosem w nasze serca, my chłopcy uważaliśmy tę armię za niezwyciężoną. Taka była nie tylko propaganda, ale tak myśmy uważali. No jak to jest możliwe, żeby ta armia w takim popłochu nagle cofała się, żeby taka dezorganizacja była, żeby w tak krótkim czasie to wszystko się, że tak powiem... ten rozpad nastąpił? To zresztą było potem głębokim, że tak powiem... odkładało się głębokim kompleksem na wojennych filmach, które zrobiłem. To było dla mnie strasznie bolesne, że to tak się stało nagle, no bo to jest ta armia, którą mój ojciec reprezentował. Co się stało, co się wydarzyło? I dlatego 17 września był w ogóle poza naszym... naszą świadomością, ponieważ nie było żadnej komunikacji, my dopiero dowiedzieliśmy się o tym, kiedy wróciliśmy z powrotem do naszego domu, kiedy dostaliśmy list od mojego ojca. Jakiś żołnierz przywiózł list i pieniądze z Szepietówki, że ojciec jest po tamtej stronie, dopiero dowiedzieliśmy się w sowieckiej niewoli. Dowiedzieliśmy się, co się wydarzyło 17 września, ale co to znaczyło niewiele wiedzieliśmy, no bo nie znaliśmy tamtych, że tak powiem, bolszewickich porządków, które były zupełnie poza nasza świadomością. I w związku z tym nieświadomość, utrzymywanie w nieświadomości społeczeństwa było... no, całkowite przez brak jakiejkolwiek swobodnej komunikacji. To prawda, że ludzie pisali różne rzeczy i dzisiaj, kiedy wypływa korespondencja z czasów okupacji, jest zdumiewające, jak w tych listach pisano o różnych rzeczach, które gdyby były kontrolowane, Niemcy by mieli lepszą kontrolę nad tym, co się działo w Polsce. No ale mieli wystarczajacą, żeby całkowicie zdezorganizować jakiekolwiek życie. Oczywiście... sam przenosiłem i sam dostawałem gazetki, które zawiadamiały nas, że się szykuje, że Londyn, że Francja, że Anglia, że nam nie pozwolą zginąć. No ale to były, że tak powiem, obiecanki, a rzeczywistość wyglądała tak jak wyglądała. Nam się wydawało, że ta klęska musi się szybko odwrócić, że to nie może być tak, że to będzie trwało w nieskończoność, tylko że wojna się skończy w ciagu kilku miesięcy, dlatego nie warto się przygotowywać specjalnie. No przeżyjemy jakoś zimę, a z wiosną, jak to wszyscy mówili, już ten na białym koniu przyjedzie do nas – to w późniejszych latach... Anders, a tutaj, że po prostu wszystko się odwróci, wojna się skończy. Myślę, że ten moment był bardzo istotny, bo pozwolił nam przetrwać te pierwsze miesiące, że co prawda klęska, ale klęska się obróci w szybkie zwycięstwo nad Niemcami. Im dłużej to trwało, tym bardziej widzieliśmy, że to nie tylko jest nasze złudzenie, ale to złudzenie się pogłębiało. Może właśnie im bardziej się pogłębiało to złudzenie, że tak powiem, odchodziło, może tym bardziej zajęcie się czym innym było taką wewnetrzną potrzebą. Ja, malując kwiaty, malując jakieś martwe natury, pejzaże jakby znajdowałem się w innym świecie i już ten świat nie mógł zrobić takiej krzywdy, dlatego że on już nie był taki dolegliwy.

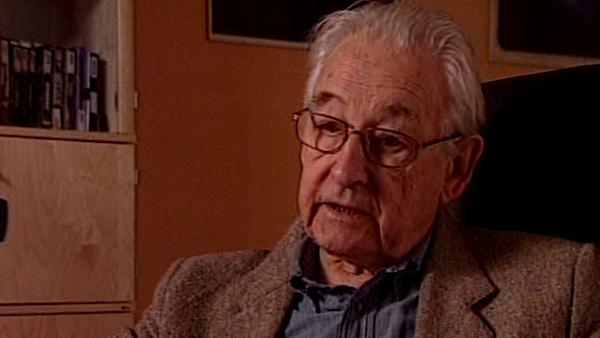

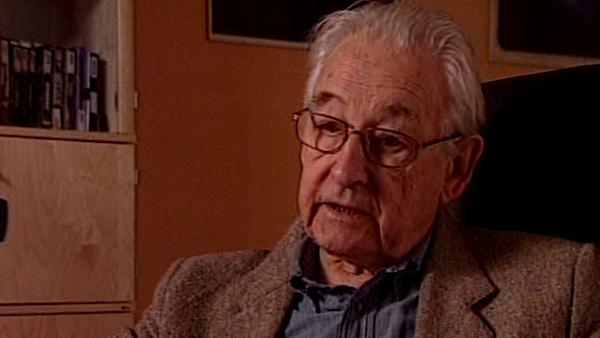

It's worth taking a moment to recall that our awareness of what was happening was very slight; this would largely explain people's behaviour during the occupation. September 17 didn't register with us at all, because together with our mother we escaped, as I've already said, to a small village close to Kazimierz on the Vistula. The chaos and the total lack of orientation of the Polish army, what happened the blow, the dreadful blow, was also a terrible blow to our hearts, we boys regarded the army as invicible. This wasn't just propaganda - we really believed this. How was it possible that the army could suddenly be retreating in such panic, for there to be such disorganisation, and for everything to have disintegrated in, I'd say, such a short time? Later, this was a deep, I'd say, it turned into a deep complex in the war films I was to make. It was acutely painful for me that this happened so suddenly because after all, this was the army my father represented. What happened, what had occurred? This is why 17 September just didn't register with us because we had no communication and we only found out about it when we returned home and got a letter and some money from my father brought to us by a soldier from Szepietówka, then we learned he was on the other side, imprisoned by the Soviets. We found out what happened on 17 September, but we didn't really know what that meant because we didn't understand the Bolshevik order which was completely beyond us. Hence the lack of awareness, people being kept unaware, was, well, the result of the lack of free communication. It's true that people wrote all kinds of things, and today, when this correspondence written during the occupation comes to light it's astonishing how people wrote about so many different things, that if the Germans had monitored these letters, they would have had more control over the things that were occurring in Poland. However, they had enough control to disorganise any sort of life. Of course, I myself distributed and received pamphlets telling us that London, France, England were all getting ready and that they wouldn't allow us to perish. However, these were, so to speak, empty promises, whereas reality was as it was. We imagined that this disaster would soon be reversed, that things can't be like this, that this wouldn't last eternally, that the war will be over within a few months and so there was no point in making any particular preparations. We managed to get through the winter and by the spring everyone was saying that a knight on a white horse would come and rescue us. Years later, that was to be Anders. Now though, everything would simply turn back, the war would end. I think this moment was very significant because it enabled us to survive the first few months: it was a disaster, but the disaster would turn into a speedy victory over the Germans. The longer it lasted, the more clearly we began to see that we were deluded and that this delusion was growing greater. Maybe the greater this delusion, I'd say the greater the need to be doing something else, it was an inner need. By painting flowers or still life or landscapes, I was entering a different world and this world could no longer do as much harm because it was no longer so troublesome.

Polish film director Andrzej Wajda (1926-2016) was a towering presence in Polish cinema for six decades. His films, showing the horror of the German occupation of Poland, won awards at Cannes and established his reputation as both story-teller and commentator on Poland's turbulent history. As well as his impressive career in TV and film, he also served on the national Senate from 1989-91.

Title: Our awareness of the war

Listeners: Jacek Petrycki

Cinematographer Jacek Petrycki was born in Poznań, Poland in 1948. He has worked extensively in Poland and throughout the world. His credits include, for Agniezka Holland, Provincial Actors (1979), Europe, Europe (1990), Shot in the Heart (2001) and Julie Walking Home (2002), for Krysztof Kieslowski numerous short films including Camera Buff (1980) and No End (1985). Other credits include Journey to the Sun (1998), directed by Jesim Ustaoglu, which won the Golden Camera 300 award at the International Film Camera Festival, Shooters (2000) and The Valley (1999), both directed by Dan Reed, Unforgiving (1993) and Betrayed (1995) by Clive Gordon both of which won the BAFTA for best factual photography. Jacek Petrycki is also a teacher and a filmmaker.

Tags: Szepietówka, Germans, Bolshevik

Duration: 5 minutes, 8 seconds

Date story recorded: August 2003

Date story went live: 24 January 2008