NEXT STORY

A deprived upbringing

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

A deprived upbringing

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11. A great knowledge of natural history | 427 | 01:11 | |

| 12. My mother and a cultural education | 471 | 02:00 | |

| 13. My father's suicide | 598 | 01:38 | |

| 14. Being an illegitimate child | 476 | 01:52 | |

| 15. Artistic parents | 421 | 02:58 | |

| 16. A developing interest in art | 391 | 05:53 | |

| 17. A deprived upbringing | 418 | 04:14 | |

| 18. Struggling to fit in at school | 414 | 05:16 | |

| 19. Unhappy schooldays and frustration with the education system | 406 | 06:29 | |

| 20. 'Most of my school friendships were based on sex' | 553 | 05:08 |

I think you’re sometimes born with things that… I know scientists will say this is impossible, but I do not remember a time when I was not interested in looking at pictures. Tiny child, going around the National Gallery. In those days, there was a day… I can’t remember whether it was Wednesday or Thursday, when you had to pay sixpence to go in, and it was called Connoisseur’s Day. And we didn’t have sixpence to spare, but that is the day on which we went. And specifically that day, because it meant that my mother could do what she wanted, which was… and this is what she did every time... we’d go to different parts of the National Gallery, which was then rather considerably smaller than it is now, and we would get to a point, and she would say, 'I want you to go into that room and find me a picture that you really like. I’m going into that room and you come and find me when you’ve decided which picture it is, and tell me why you like it'.

Now that’s very different from just saying, 'I like it'. And as a child, you come up with some fairly puerile reasons. And I remember a number of pictures. Well, the Dürer, for example, the so-called Dürer, Red Madonna, which I adored, because it was red. All other Madonnas were blue and this was different. And the Madonna has fair, curly hair in sort of wiry curls. And this, again, is different, and so I had reasons for liking this picture, of which I could tell her, and did.

And it starts at that pretty basic level: I like it because of a colour or this sort of thing. But eventually, you begin to find other reasons for liking it. And so seeing pictures again and again and again, your perception of them, even if you’re only a child, begins to deepen. But that’s how it began. It was cut short by the War. It was in 1939, everything was taken down. In 1939, I was eight. Everything was taken down and went away. But then, of course, the Gallery recovered, in the sense of having… it brought back a picture, a different picture, every month from the slate quarries. And took extraordinary risks. I mean, they brought back the Velázquez Rokeby Venus, and it was rather like the little exhibitions which the National Gallery runs from time to time, just putting one great picture in a room, and that’s it. And it compels you to contemplate.

So looking intently at a picture, because it’s the only picture, became a practice. And then exhibitions by… paintings by Sickert, I think, in 1942... Augustus John, the War artists, John Piper, all sorts of people. They would have an exhibition for a month or so. And... so my experience of pictures broadened from the Old Masters at which I’d been looking in the Tate and the National, to things that were actually being done more or less then. So I was, as it were, with it at the time. It was all hugely important.

When the War came to an end, extraordinary things happened, so quickly. 1945, the National Gallery... the National Gallery, had an exhibition of, I think, something like 150 paintings by Paul Klee. I mean, just think of it. Darkness and dereliction. The War is just over, we’ve none of us got any food or any money. A lot of people with no work, no housing, no repairs to any of the devastation that had happened to London. And there’s the National Gallery offering us Paul Klee, of all people.

And the V&A... the V&A… again, the astonishing sort of… the brilliance of the idea, of the V&A putting on an exhibition that winter of Picasso and Matisse. I mean, you know, astonishing. We had a bunch of wartime Picassos, which are in my view, now, the worst of all, on the walls of V&A. It was wonderful the way London came to life so quickly. And in the most unlikely places, efforts were being made to nourish the spiritual side of the... and the intellectual side of the nation.

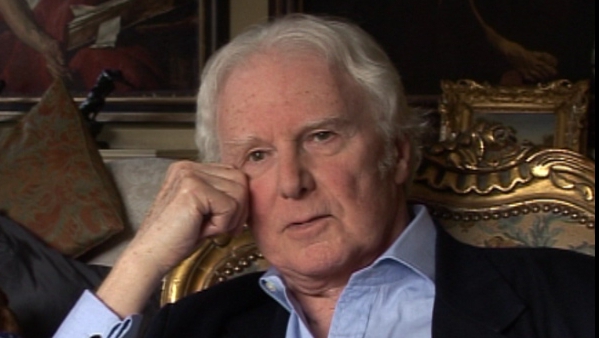

Born in England, Brian Sewell (1931-2015) was considered to be one of Britain’s most prominent and outspoken art critics. He was educated at the Courtauld Institute of Art and subsequently became an art critic for the London Evening Standard; he received numerous awards for his work in journalism. Sewell also presented several television documentaries, including an arts travelogue called The Naked Pilgrim in 2003. He talked candidly about the prejudice he endured because of his sexuality.

Title: A developing interest in art

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is an independent documentary producer who has made a number of films about science and scientists for BBC TV, Channel Four, and PBS.

Tags: National Gallery, World War II, Rokeby Venus, Tate, The Victoria and Albert Museum, London, Red Madonna, The Madonna with the Iris, Mary Jessica Perkins, Albrecht Dürer, Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez, Walter Richard Sickert, Augustus Edwin John, John Egerton Christmas Piper, Paul Klee, Pablo Picasso, Henri Émile Benoît Matisse

Duration: 5 minutes, 53 seconds

Date story recorded: 2008

Date story went live: 28 June 2012