NEXT STORY

The future of open access and retractions in citations

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

The future of open access and retractions in citations

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 61. A job offer and teaching at the University of Pennsylvania | 41 | 03:06 | |

| 62. Sharing information and encyclopedists | 47 | 04:43 | |

| 63. The Atlas of Science | 46 | 02:59 | |

| 64. The Atlas of Science as a dynamic projection | 36 | 02:02 | |

| 65. Algorithmic and historiographic analysis | 37 | 06:38 | |

| 66. The future of open access and retractions in citations | 49 | 05:02 | |

| 67. Duplication in research and a citator for patents | 33 | 04:40 | |

| 68. Citing in patents and papers | 46 | 05:52 | |

| 69. Errors and how they affect retreival | 34 | 03:01 | |

| 70. The mathematics in papers today | 53 | 01:31 |

After that we did that DNA, writing the history of DNA with citation data, we always talked about the idea of being able to do that in a kind of automatic, semi-automatic, algorithmic fashion. And about 5e years ago I was talking to Sacha Pudovkin about that project, and I don’t remember the exact sequence, he probably remembers it better than I do, we decided why don’t we... why don’t we now try it because things have changed, we have the computer power and so forth, and so we began to do the programmes for doing that. And as a result of that work... and then we brought in Vladimir Istomin, his former student from Siberia, who was at the University of... Washington State University at the time. So, he started to do the programming, you know, all the programming. He was a very clever programmer. That’s how we got into his site, doing these algorithmic historiographic analyses. And the software is now going to be available; I believe next week is the launch, in the next week or two. Because they had done the final touches on, you know, whatever they have to do for a commercial programme. And I think ISI is going to help the marketing of it, so we’ll see where that goes. But basically people are going to have to learn a little about modulating that kind of information because it doesn’t work out as simply as you would like. Some of the things are very straightforward. I mean, you just do a typical search of a subject, like you don’t have to do a complete subject, you just do, let’s say, download 1,000 references from WOS, and you identify right away that sample, the 50 most important papers in the field based on the frequency analysis and so forth, and you get a nice looking little map, depending on how complex the field is. But some of the time you think you’re going to be able to prove a point and it doesn’t work out quite as well because there’s, there’s this variation in the way that people cite the literature that doesn’t always show you the micro links. I think in a macro sense it works perfectly well because the citation frequencies are so large that it doesn’t matter whether you make small mistakes. But if you got something that was linked by one or two references, you know, you could easily lose it. And if you want to display more than 200 nodes at a time it gets to be difficult on that limited screen. That’s why I mentioned that huge screen because, you know, you get a big screen and you can do a lot more with it and see some of the connections that you would otherwise miss. Because whenever I, whenever I go back and try to trace the history of something I learn something new every time I look in the file. And it turns out that what the software now does, in comparison with what it first did, we used to separate what we called inter and outer references, now it just generates one complete citation index for the file right away, and you can separate them, and you can either have both or all, and then you get a timeline right away; there is a time line with a subject. Depending... what happens is you get enough people who have written on a subject collectively they produce a pretty comprehensive history in the field, I mean it’s all there. If these people aren’t going to give you the information, who will? It’s sort of like a given thing, unless you’re going into some obscure subject that nobody’s ever really written about, and in that case you wouldn’t find any references anyhow. So, I think that ought to prove to be of interest to a lot of people when it gets to be more widely used. But I’ve always, I’ve always encountered resistance to this sort of thing by trained historians, you know; they don’t trust that stuff, it’s got to be subjective, the old fashioned way of doing it. You’ve got to read it all first and then you produce the analysis. It’s like when I was at the Welch Medical Library I used to go to the lectures by Oswei Temkin, a very famous historian of medicine who was located there, and one time somebody went to one of his lectures and asked a question which involved... making implicitly... the answer that Temkin gave was, 'The answer to your question is if it was there I would have read it'. Meaning he had read everything ever written on that subject, in any language you could think of, including six or seven languages. That’s not the way it is today. I don’t know if that would have been true if Henry Sigerist or others like him ever meet me, or whatever. Bob Morton was a kind of guy who read a lot, and his recollection was incredible too, memory. Anyhow you would hope that ultimately when all this stuff gets put up on the web and it’s in books and everywhere else is completely visual, we’ll be able to get some very interesting historical analyses, but I guess we’re going to have to modify all the different softwares to take advantage of all the full text that will be available. Because right now we’re dependent on databases like WOS or Scopus or Google or whatever, but when you do the full text you are going to have to have different software written to take advantage of all that stuff, and then do your mapping. So, there’s a lot more to be done yet.

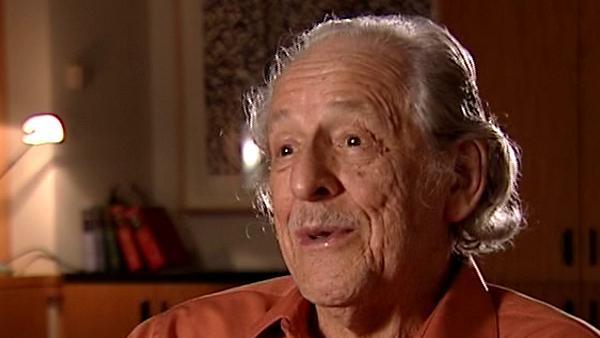

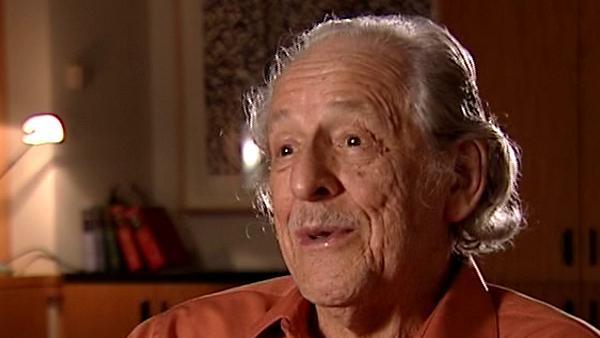

Eugene Garfield (1925-2017) was an American scientist and publisher. In 1960 Garfield set up the Institute for Scientific Information which produced, among many other things, the Science Citation Index and fulfilled his dream of a multidisciplinary citation index. The impact of this is incalculable: without Garfield’s pioneering work, the field of scientometrics would have a very different landscape, and the study of scholarly communication would be considerably poorer.

Title: Algorithmic and historiographic analysis

Listeners: Henry Small

Henry Small is currently serving part-time as a research scientist at Thomson Reuters. He was formerly the director of research services and chief scientist. He received a joint PhD in chemistry and the history of science from the University of Wisconsin. He began his career as a historian of science at the American Institute of Physics' Center for History and Philosophy of Physics where he served as interim director until joining ISI (now Thomson Reuters) in 1972. He has published over 100 papers and book chapters on topics in citation analysis and the mapping of science. Dr Small is a Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, an Honorary Fellow of the National Federation of Abstracting and Information Services, and past president of the International Society for Scientometrics and Infometrics. His current research interests include the use of co-citation contexts to understand the nature of inter-disciplinary versus intra-disciplinary science as revealed by science mapping.

Duration: 6 minutes, 38 seconds

Date story recorded: September 2007

Date story went live: 23 June 2009