NEXT STORY

The difference between precision and accuracy

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

The difference between precision and accuracy

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. The box that attracted me to science | 1 | 1012 | 01:37 |

| 2. My scientific education | 2 | 403 | 03:59 |

| 3. The difference between precision and accuracy | 468 | 04:26 | |

| 4. On being a human guinea pig | 1 | 274 | 03:10 |

| 5. How JBS Haldane made his liver fizz | 2 | 644 | 00:42 |

| 6. Health and safety hampers science today | 306 | 01:06 | |

| 7. How I invented the electron capture detector | 428 | 06:10 | |

| 8. What is the meaning of life? | 2 | 526 | 04:12 |

| 9. An invitation from NASA | 3 | 297 | 02:51 |

| 10. Detecting life on Mars | 1 | 344 | 04:20 |

The next step in my science education was when the whole family, we moved to Brixton in South London and my mother and father ran an art shop there. It's a crazy thing to do because of all the neighbourhoods in which to sell up market stuff like that nowhere was worse than Brixton, but they were a bit crazy in some ways.

And my mother was a great reader and she took me along when I was about seven years old to the Brixton library and I used to pick up books, at first there on science fiction and that kind of thing, like HG Wells and Jules Verne and so on. But soon I moved onto hard stuff and discovered they had a basement in the library which was full of textbooks on science. And by the time I was eight I was avidly reading Wade's Organic Chemistry and Jeans' Astronomy and Cosmogony and Soddy's The Discovery of Radium. And for biology my favourite was JBS Haldane, especially the experiments he did on himself. And in that I was interested to discover that he was also John Maynard Smith's hero. Maynard Smith was lucky enough to go to work with him, but all I had was his books which were wonderful inspiration.

But all of that reading turned me onto science and gave me a kind of grounding right the way across without any disciplinary barriers. And when I went to grammar school I found the science taught was almost unbelievably dull and took very little notice of it. And that kind of started me out in... in science and I kept an interest in it and I think you've got to have that. You've got to be turned onto something, if it's going to be your life's work. It's not something you can just sort of decide to do in your teens and think this'll be a good career. It's got to be a vocation and when I was young I wanted nothing more than to be able to work in a lab for the rest of my life. That was my, going to be my life.

I was lucky because my parents were fairly poor. Their art shop completely collapsed in the depression and there was no way that they could afford to have me go to university. It wasn't a matter of getting a... a scholarship there or a grant to go to university, it was the matter of they needed my income and I left school to support the family. And so, I got a job as a technician for a firm of consultants in London and I was very lucky, it was run by a man who looked a bit like Mr Pickwick. He was rather plump and very amiable and affable and he spoke with an accent like the old actor George Sanders. I don't know whether you can remember him. Very British upper-class kind of accent, very plummy. And, but he was a wonderful teacher and he taught me that science is really serious, that if you're doing analyses and, they actually, what they worked for was the photographic industry. They covered all aspects from the gelatine used to make the film to the dyes used for colour photography and so on right the way across the board. They took on odd jobs like making fingerprint powders for Scotland Yard and so on. And, anyway, he taught me that I must get all the analyses I did for him absolutely right. There was to be no fudging and no halfway, and if I was just to tell him because it was okay if I thought I had made a mistake. That didn't matter. The worst thing I could do would be to put in a false answer. And after months and months of training I began to realise how right he was.

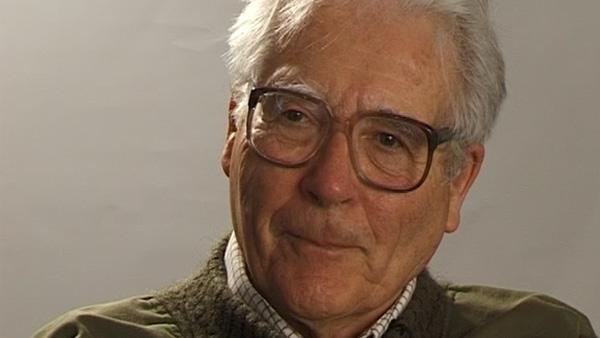

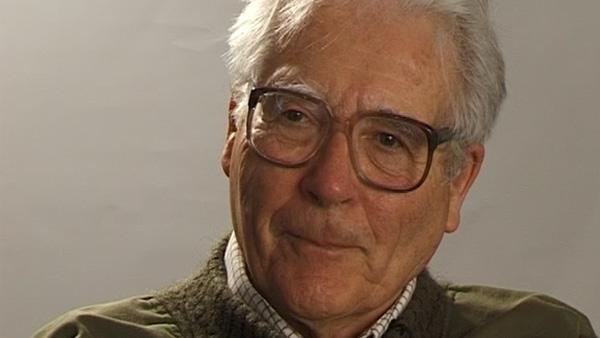

Born in Britain in 1919, independent scientist and environmentalist James Lovelock has worked for NASA and MI5. Before taking up a Medical Research Council post at the Institute for Medical Research in London, Lovelock studied chemistry at the University of Manchester. In 1948, he obtained a PhD in medicine at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and also conducted research at Yale and Harvard University in the USA. Lovelock invented the electron capture detector, but is perhaps most widely known for proposing the Gaia hypothesis. This ecological theory postulates that the biosphere and the physical components of the Earth form a complex, self-regulating entity that maintains the climatic and biogeochemical conditions on Earth and keep it healthy.

Title: My scientific education

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is a London-based television producer and director who has made a number of documentary films for BBC TV, Channel 4 and PBS.

Tags: Brixton, South London, Brixton Library, Organic Chemistry, Astronomy and Cosmogony, HG Wells, Jules Verne, LG Wade, James Jeans, Frederick Soddy, JBS Haldane, John Maynard Smith, George Sanders

Duration: 3 minutes, 59 seconds

Date story recorded: 2001

Date story went live: 21 July 2010