NEXT STORY

Filming slime mold as it grows

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Filming slime mold as it grows

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 21. My inferiority complex | 175 | 01:28 | |

| 22. The inimitable William H Weston | 77 | 03:33 | |

| 23. A serendipitous discovery | 72 | 02:02 | |

| 24. Upstaged by slime molds | 70 | 02:30 | |

| 25. How slime molds grow | 65 | 03:08 | |

| 26. My eureka moment | 101 | 03:11 | |

| 27. Filming slime mold as it grows | 97 | 03:10 | |

| 28. What makes slime mold grow at right angles? | 57 | 03:29 | |

| 29. Ammonia is it! | 44 | 01:22 | |

| 30. Complemented on my thesis | 1 | 43 | 00:41 |

There was a man named Paul Weiss who was a brilliant, wonderful embryologist who was at the Rockefeller University, who I knew. And he kept saying to me, 'Check everything else before you say its chemotaxis because it probably isn't chemotaxis'. And he thought it was some sort of what he called 'contact guidance' where they were sort of feeling their way along; exactly how it's not clear. And so my whole thesis was to try and show that it had to be chemotaxis. And after I got out of the army, I had a few months to finish my thesis. And relatively early in that few months, I hit the solution. It was one of those wonderful eurekas that had me dancing in the lab and punching the air and so forth, because I instantly looked through the scope and could see that it was chemotaxis. And here's what I saw. I had a bunch of aggregates forming in a round dish and a stirring rod slowly making a circular current. And then what happened was I would go off into another room and do something else, not thinking this is going to be very much. But I looked at the scope 20 minutes later and I just nearly fell through the ceiling. What I saw was that you could see that where they… it's like looking at smoke going from burning piles of leaves in the autumn: the wind was blowing the smoke one way and so you didn't have any smoke up above. And here, you found that the amoebae up above had no idea where the centre was, but the ones down below were forming these long trails that go towards it. And so instantly, I realised that I can get my degree now. And although it was interesting that some of my professors at my final exam were very un-nice about that because they said, 'Why don't you know what the substance is?' and I got very defensive. But anyhow, I didn't do that until years later. I eventually did, but that's another story.

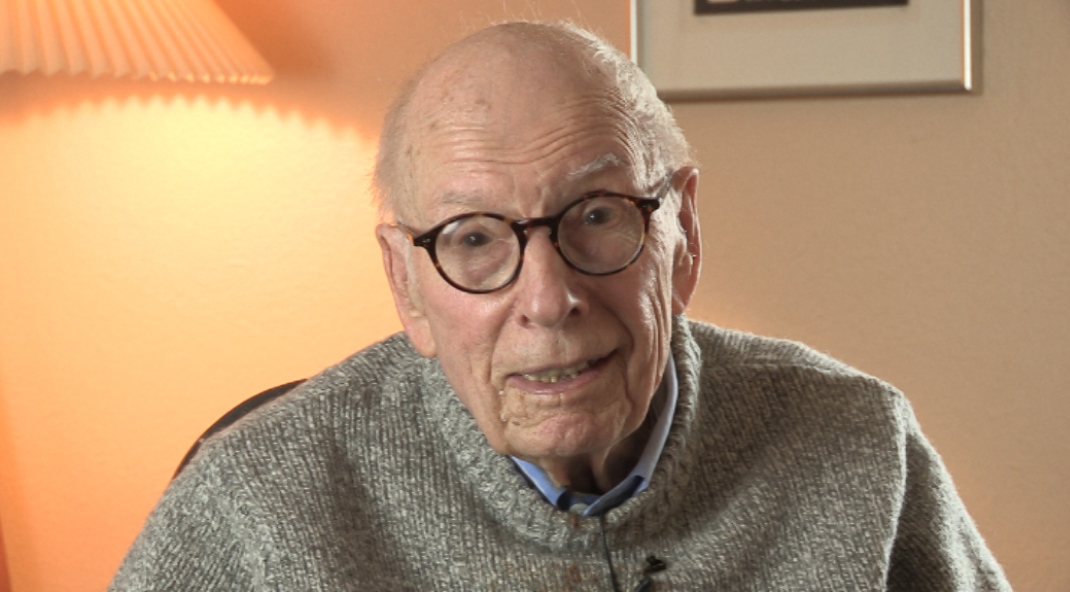

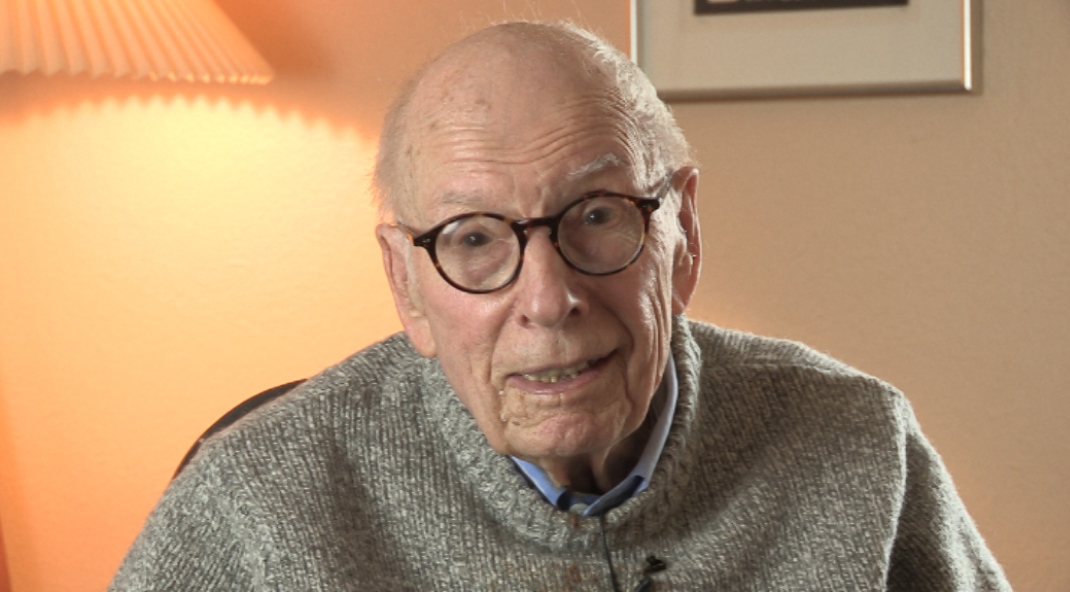

John Tyler Bonner (born in 1920) is an emeritus professor in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at Princeton University. He is a pioneer in the use of cellular slime molds to understand evolution and development and is one of the world's leading experts on cellular slime molds. He says that his prime interests are in evolution and development and that he uses the cellular slime molds as a tool to seek an understanding of those twin disciplines. He has written several books on developmental biology and evolution, many scientific papers, and has produced a number of works in biology. He has led the way in making Dictyostelium discoideum a model organism central to examining some of the major questions in experimental biology.

Title: My eureka moment

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is an independent documentary producer who has made a number of films about science and scientists for BBC TV, Channel Four, and PBS.

Tags: chemotaxis, amoebae, microscope, aggregates

Duration: 3 minutes, 11 seconds

Date story recorded: February 2016

Date story went live: 14 September 2016