NEXT STORY

Another visit to The Institute for Advanced study. Shiing-Shen Chern

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Another visit to The Institute for Advanced study. Shiing-Shen Chern

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 61. Isotopic spin | 1104 | 03:37 | |

| 62. Explaining Dave Peaslee's letter | 949 | 04:17 | |

| 63. Giving talks on the idea of isotopic spin | 898 | 03:46 | |

| 64. Almost getting drafted; a letter to the Physical Review | 1065 | 02:05 | |

| 65. Problems with the letter to the Physical Review | 1122 | 03:50 | |

| 66. Talking to Fermi, the theory of high angular momentum | 1275 | 04:38 | |

| 67. Confirming the theory | 925 | 02:41 | |

| 68. The role of Pais; associated production | 1037 | 00:53 | |

| 69. Associated production, isotopic spin and strangeness | 750 | 01:04 | |

| 70. Giving a class in Chicago. Presenting a paper with Pais | 1081 | 04:02 |

I gave a class at Chicago which was attended by Fermi, and when Fermi came to anyone else's lecture, whether it was a seminar or a class or whatever, if he didn't like or understand something he would just stop the proceedings right there and not allow anything to go on until he was satisfied. And if it took him till the next lecture or the one after that he would still stubbornly refuse to allow anything to happen, he'd just keep asking his questions and making his objections over and over again. Well in my class he objected to this idea of K0 and K0-bar, because he said, ‘Can't you take the sum and the difference?’ Well, I knew all about that because of my controversy with the Physical Review and my checking over Nick Kemmer's paper of 1937, so I was able to answer him. I said, ‘Yes, you're absolutely right, and the K0 and K0-bar can be looked at in terms of their sum and the difference. However, in production it's the K0 and the K0-bar that matters, because K0 is allowed under certain circumstances while K0-bar is forbidden.’ and so on. So in a production reaction those are the relevant states. But in a decay it may vary and in many cases it may be that it's the sum and the difference that have particular decay properties, particularly if charge conjugation is involved. Well, after a while he accepted that. But then I developed that further and as I developed it I was in communication with Pais. We worked together a little bit. In the summer of ’54 we presented a paper together in Glasgow with my correct ideas and his wrong ideas. And… and then we also presented a model that we developed together which included strangeness but included extra particles as well as the ones that were known, so as to shift the centre of charge of the whole system back to plus a half. So that meant that besides the lambda there was also a positive analogue of the lambda which was an isotopic singlet and so on and so forth. Well, what we were doing was really inventing charm. We left out a couple of states with charm but almost… it was almost a correct presentation of charm. But with a very unphysical hypothesis that the charm mass was similar to the strange mass, that the charm… the mass difference occasioned by charm was not very different from the mass difference occasioned by strangeness–which is of course totally wrong. But if you ignore that then what we presented was extremely close to the charm model, so we presented three models in Glasgow. Anyway, after that we continued to work together a little bit and we explored this matter of the K01 and K02. I really had had all the ideas myself, with the aid of Fermi's question, and I thank Fermi, at the end of the paper. It says, 'One of us wishes to thank Enrico Fermi for a very interesting discussion.' It was something like that. But I wrote it up with Pais anyway; I was feeling generous.

[Q] He was at the institute at the time?

Yes. And I thought I would write it up with him even though he hadn't really contributed anything significant. I didn't realize then that he made a habit of sort of seizing credit for things, or I would have protested, but I was quite relaxed about it at the time.

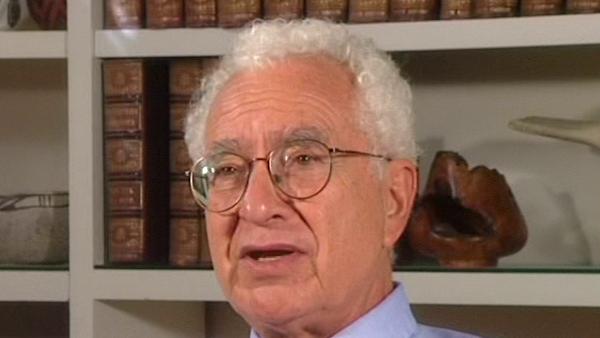

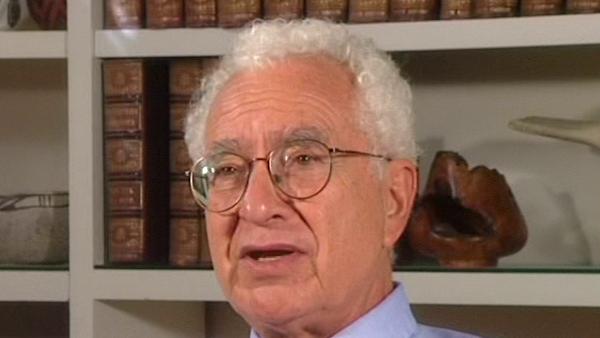

New York-born physicist Murray Gell-Mann (1929-2019) was known for his creation of the eightfold way, an ordering system for subatomic particles, comparable to the periodic table. His discovery of the omega-minus particle filled a gap in the system, brought the theory wide acceptance and led to Gell-Mann's winning the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1969.

Title: Giving a class in Chicago. Presenting a paper with Pais

Listeners: Geoffrey West

Geoffrey West is a Staff Member, Fellow, and Program Manager for High Energy Physics at Los Alamos National Laboratory. He is also a member of The Santa Fe Institute. He is a native of England and was educated at Cambridge University (B.A. 1961). He received his Ph.D. from Stanford University in 1966 followed by post-doctoral appointments at Cornell and Harvard Universities. He returned to Stanford as a faculty member in 1970. He left to build and lead the Theoretical High Energy Physics Group at Los Alamos. He has numerous scientific publications including the editing of three books. His primary interest has been in fundamental questions in Physics, especially those concerning the elementary particles and their interactions. His long-term fascination in general scaling phenomena grew out of his work on scaling in quantum chromodynamics and the unification of all forces of nature. In 1996 this evolved into the highly productive collaboration with James Brown and Brian Enquist on the origin of allometric scaling laws in biology and the development of realistic quantitative models that analyse the influence of size on the structural and functional design of organisms.

Tags: University of Chicago, Institute of Nuclear Studies, Physical Review, Glasgow, Abraham Pais, Enrico Fermi, Nick Kemmer

Duration: 4 minutes, 3 seconds

Date story recorded: October 1997

Date story went live: 24 January 2008