NEXT STORY

New topics for films

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

New topics for films

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 91. Roly Poly: My first comedy | 47 | 04:21 | |

| 92. Roly Poly: The need to create a contemporary film | 36 | 00:57 | |

| 93. Everything for Sale: A film about Zbyszek Cybulski | 93 | 04:06 | |

| 94. Everything for Sale: The cast | 82 | 02:02 | |

| 95. Everything for Sale as a great challenge | 62 | 04:35 | |

| 96. The shameful year of 1968 | 68 | 03:32 | |

| 97. Hunting for Flies | 50 | 01:41 | |

| 98. Birchwood | 73 | 04:32 | |

| 99. Birchwood: A new look at nature | 48 | 03:53 | |

| 100. Paintings of Jacek Malczewski in Birchwood | 120 | 04:03 |

Kiedy przeczytałem tą opowieść Jarosława Iwaszkiewicza, oczywiście odpowiednikiem w polskim malarstwie stanęły mi od razu przed oczami obrazy śmierci namalowane przez Jacka Malczewskiego. To było zupełnie oczywiste, że nie ma lepszego odniesienia i wyrazistszego odniesienia. W związku z tym poprosiłem, żeby Muzeum Narodowe w Warszawie wypożyczyło mi obraz Jacka Malczewskiego do miejsca, gdzie my robiliśmy zdjęcia. My robiliśmy zdjęcia w takiej leśniczówce, przez okna widać było brzezinę. Bodajże po tylu latach, ja wróciłem w tą samą brzezinę, żeby zrobić tam zdjęcia do Pana Tadeusza, w międzyczasie te drzewa zrobiły się dużo grubsze, wyginęła cała ta... to wszystko, co tam rosło pomiędzy tymi drzewami. No i znalazłem się w innym świecie, w jakby takiej no... kościele, jakiejś wspaniałej budowli z tych wspaniałych, wielkich, starych brzóz. Wtedy te brzozy były znacznie mniejsze, jeszcze poszycie było pomiędzy nimi. No ale wszystko to bardzo było bliskie malarstwa... malarstwa Jacka Malczewskiego i ten obraz, który zawisł tam w tej dekoracji nie był tylko po to, żeby go sfotografować, ale też był po to, żeby mnie stale przypominać, gdzieś z tyłu głowy, co... do czego, jakby do jakiego malarstwa, do jakiej sztuki ja nawiązuję. A to było piękne, dlatego że w opowiadaniu Iwaszkiewicza była też jakaś głęboka tajemnica, tajemnica śmierci tego brata, który odchodzi. Tej gwałtownej miłości tego drugiego. Miłość ze śmiercią się łączy równocześnie, to że on umiera na wiosnę, a jak sam mówi tam w dialogu – to jest najsmutniejsze umierać na wiosnę, kiedy wszystko się budzi, wszystko będzie życiem, a jego życie, tego... tego młodego człowieka, kończy się. Ten fortepian, który najpierw przyjeżdeża, a potem wyjeżdża i właściwie jak trumna opuszcza tę leśniczówkę. Wszystko to były sceny, które były bliskie właśnie temu, czym jest malarstwo Jacka Malczewskiego, ale robiłem to z całą świadomością. Ciekawe bardzo, że autor opowiadania Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz, gdy zobaczył ten film, najbardziej zdziwił się właśnie temu, że ja się odwołałem do Jacka Malczewskiego. Mówi: 'Słuchaj' – w trzydziestych latach, nie pamiętam, w '32 roku chyba, Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz pisał to opowiadanie, a może wcześniej, mówi – 'słuchaj, dla nas Jacek Malczewski to było najbardziej nieudane polskie malarstwo. To było to, co nas odpychało; to, co nas odrzucało. Jakim sposobem ty mogłeś moje opowiadania połączyć z Malczewskim, z malarstwem Malczewskiego?'. Nie miał tego jako wyrzut, dlatego że myślę, że to się dobrze sprawdziło to malarstwo, że tak powiem, te obrazy nabrały siły i wyrazistości. Ale był zdumiony, że ja odwołuję się do czegoś, co w tej epoce, kiedy on pisał swoje opowiadanie, było synonimem kiczu, synonimem tego, że tak powiem, co jest w złym guście.

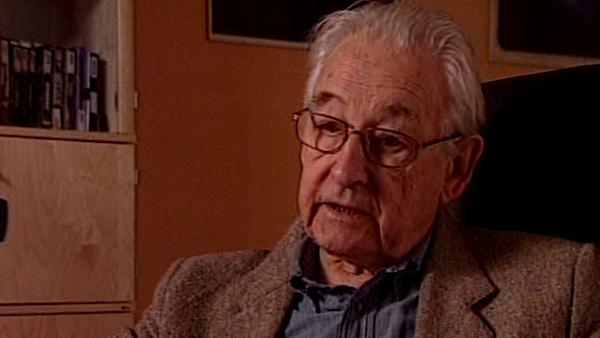

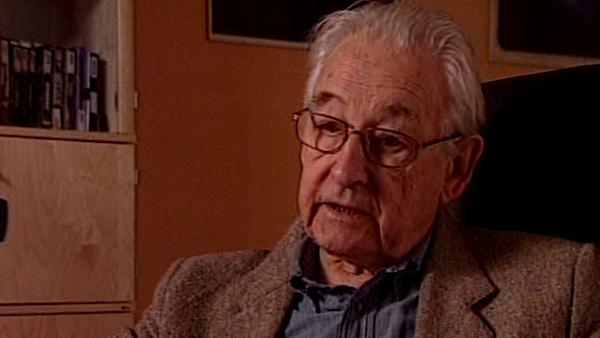

When I'd read Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz's story, an image was immediately conjured up of the equivalent in Polish art: the paintings by Jacek Malczewski depicting death. It was quite obvious that there was no better and no clearer equivalent. Because of this, I asked the National Museum in Warsaw to lend me a painting by Jacek Malczewski to use in the location where we would be filming. We were filming in a hunting lodge and through its windows you could see a birch grove. Years later, I went back to the same birch grove to film Pan Tadeusz. In that time, the trees had grown much thicker and everything that had been growing on the ground between them had died. Now I found myself in a different world as if I were in a church whose magnificent construction was made from these magnificent old birches. Then, these birches had been much smaller and there had been undergrowth between each of them. All of this had been closer to the art of Jacek Malczewski, and that painting that was hung there on the set wasn't there just so that we could film it, but also so that it could remind me constantly, somewhere in the back of my head, of what, which type of art I was referring to. This was beautiful, because in Iwaszkiewicz's story, there's a profound mystery of the death of this brother who departs. The intense love of the other. Love and death are joined. The fact that he dies in the Spring, and as he says himself, the saddest thing of all is to die in the Spring when everything is awakening, everything will be alive, while his life, the life of a young man is ending. This piano which first arrives and then departs, leaving the lodge like a coffin. These were all scenes that were closely reminiscent of what consituted Jacek Malczewski's paintings, but I did this deliberately. It's interesting that the author of the story, Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz, on seeing the film, was astonished that I had referred to Jacek Malczewski. He said, 'Listen', in the 30s, I don't remember perhaps it was '32 when Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz had written this story or perhaps it was earlier, he said, 'Listen, in our eyes, Jacek Malczewski was the least successful Polish painter. His art was repulsive, it was repellant. How could you connect my story with Malczewski and with Malczewski's paintings?' He wasn't saying this as an accustion because I think these paintings worked, they aquired strength and clarity. But he was amazed that I was referring to something which, at the time when he was writing his story, was synonymous with kitsch and with everything that was in bad taste.

Polish film director Andrzej Wajda (1926-2016) was a towering presence in Polish cinema for six decades. His films, showing the horror of the German occupation of Poland, won awards at Cannes and established his reputation as both story-teller and commentator on Poland's turbulent history. As well as his impressive career in TV and film, he also served on the national Senate from 1989-91.

Title: Paintings of Jacek Malczewski in "Birchwood"

Listeners: Jacek Petrycki

Cinematographer Jacek Petrycki was born in Poznań, Poland in 1948. He has worked extensively in Poland and throughout the world. His credits include, for Agniezka Holland, Provincial Actors (1979), Europe, Europe (1990), Shot in the Heart (2001) and Julie Walking Home (2002), for Krysztof Kieslowski numerous short films including Camera Buff (1980) and No End (1985). Other credits include Journey to the Sun (1998), directed by Jesim Ustaoglu, which won the Golden Camera 300 award at the International Film Camera Festival, Shooters (2000) and The Valley (1999), both directed by Dan Reed, Unforgiving (1993) and Betrayed (1995) by Clive Gordon both of which won the BAFTA for best factual photography. Jacek Petrycki is also a teacher and a filmmaker.

Tags: Pan Tadeusz, Jacek Malczewski, Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz

Duration: 4 minutes, 3 seconds

Date story recorded: August 2003

Date story went live: 24 January 2008