NEXT STORY

The music for The Devils

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

The music for The Devils

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 191. New culture | 29 | 02:52 | |

| 192. Hatful of Rain | 22 | 04:22 | |

| 193. Zbigniew Cybulski in the theatre | 58 | 05:02 | |

| 194. Subsequent theatre plays | 16 | 01:48 | |

| 195. A lesson in directing from Tadeusz Łomnicki | 33 | 04:19 | |

| 196. The Wedding in theatre | 20 | 01:16 | |

| 197. Dostoyevsky's The Devils | 57 | 02:24 | |

| 198. The Devils and the new nationalists | 50 | 03:12 | |

| 199. Dostoyevsky's prompts | 39 | 02:56 | |

| 200. The influence of Japanese theatre on The Devils | 41 | 03:57 |

By a lucky coincidence while I was working on The Devils, I went to Japan for the first time in my life to take part in a film festival where a Polish film was being screened. I had been invited separately. This was in 1960 when the world exhibition was being held in Osaka. I saw for the first time that marvellous architecture, new electronic inventions, but this wasn't what mattered the most. What was most important was my meeting with a professor who taught Polish at the University in Tokyo. He turned out to be an American, born and bred, who had nothing whatsoever to do with Poland except for the fact that he had spent one year studying at the Jagiellonian University. He had learned to speak Polish fantastically well and now lectured on Polish literature in Japanese, of course. He told me, 'You have to see Japanese theatre, you have to see Bunraku which is puppet theatre and is the most original theatre.' What did I see? I managed to go to a performance in Osaka, which wasn't easy, and I saw the theatre of my dreams. The puppets used in Bunraku theatre are large, about this size, and each one is operated by three people. One main operator moves the head, animating the eyes and the mouth. He holds his hand in the puppet's head and moves its torso. Another, who stands behind him, moves the puppet's arms and another moves its legs. So three people are holding the puppet and I have to say the effect on someone seeing this for the first time is amazing because you see a living... the puppet is alive while they do everything to stop it from jumping into the audience and mixing with us. It's amazing. On top of this, all of the people are dressed in black and the assistants have their faces covered. Someone had to carry the furniture in and out because I needed some sort of theatrical marker to show whether it was the drawing room or Szatow's home or Kiryłow's. There had to be something to distinguish these different scenes from one another so furniture, screens, things of this kind showed us where we were. But all of this had to be carried in and out. So when I returned to Kraków, I decided that these black characters were good. They are called 'kuroko' and are there to serve. They are servants. They bring on the props. For someone who is seeing this theatre for the first time, they are more exciting than the rest, but for the Japanese public they are simply servants who are necessary so that the action on stage can be animated. The same characters appear in the traditional Japanese theatre of Kabuki. They, too, bring in different things. When I introduced these characters, it turned out that this was a good idea. The stage lighting was dimmed a bit and suddenly these strange creatures appeared, dressed in black, who carried off the old sets and brought in new ones.

Szczęśliwym trafem w tym czasie jak pracowałem nad Biesami pojechałem do Japonii, pierwszy raz zresztą w życiu, żeby wziąć udział w takim...w takim festiwalu filmów, gdzie był też i jeden z polskich filmów. Mnie zaprosili osobno. A też to było w '60 roku, bo była wystawa w Osaka, światowa. Pierwszy raz zobaczyłem właśnie tę wspaniałą nową architekturę, nowe wynalazki elektroniczne, ale nie to było najważniejsze. Najważniejsze było to, że poznałem profesora, który uczył języka polskiego w Tokyo na uniwersytecie, który okazał się być Amerykaninem, rodowitym, nie mającym nic wspólnego z Polską, poza tym, że był przez rok studentem Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego. Nauczył się mówić po polsku fantastycznie, no i wykładał polską literaturę po japońsku oczywiście. On powiedział mi: 'Pan musi zobaczyć japoński teatr, musi Pan zobaczyć teatr Bunraku – to jest teatr lalkowy, to jest najbardziej oryginalny teatr'. Co ja zobaczyłem? Rzeczywiście w Osaka udało mi się dostać na przedstawienie, co nie było łatwe i zobaczyłem teatr po prostu moich marzeń. Lalki teatru Bunraku są duże, takiej wielkości i każda z nich animowana jest przez trzech ludzi. Jeden główny animator porusza głową, a poruszają się i oczy, i usta. Ma rękę w głowie i jakby porusza tułowiem. Jeden stojący za jego plecami porusza rękami tej lalki, a jeden porusza nogami tej lalki. Tak że trzy osoby trzymają tę lalkę i muszę powiedzieć, że efekt jest dla kogoś, kto patrzy pierwszy raz zdumiewający, bo widzisz żywą... to co jest żywe, to jest ta lalka, a oni robią wszystko, żeby ona nie wyskoczyła na widownię i z nami się nie zadała. Zdumiewające. Jeszcze w dodatku okazuje się, że wszystkie te postaci ubrane są na czarno i ci pomocnicy mają zakryte twarze. A ponieważ ktoś musiał wnosić i wynosić meble, bo sztuka dzieje się w różnych sceneriach i potrzebowałem jakiegoś zaznaczenia teatralnego, że to jest salon, a to jest mieszkanie Szatowa, a to jest mieszkanie Kiryłowa. Jakaś różnica, że tak powiem, pomiędzy tymi sceneriami musiała nastąpić, więc meble, parawany, jakieś elementy tego rodzaju miały zaznaczyć gdzie my jesteśmy. No ale to trzeba wnieść i wynieść. No i kiedy wróciłem do Krakowa, pomyślałem, że te czarne postacie są dobre. Oni się zresztą nazywają kuroko. To są postacie, które służą. To jest służący. Oni przynoszą rekwizyty. Dla kogoś, kto widzi pierwszy raz ten teatr oni są bardziej ekscytujący niż cała reszta. Ale dla japońskiej publiczności to jest po prostu służba, która jest konieczna, żeby zaanimować to wszystko, co jest... się dzieje na scenie. Te same postacie zresztą występują też w tradycyjnym teatrze japońskim, w teatrze kabuki. Też właśnie przynoszą różne rzeczy. I jak zrobiłem te postacie, okazało się, że to jest dobry pomysł. Przyciemnia się nieco światło i nagle wpadają jakieś dziwne stwory, czarno ubrane, które te dekoracje szybko wynoszą, wnoszą następne.

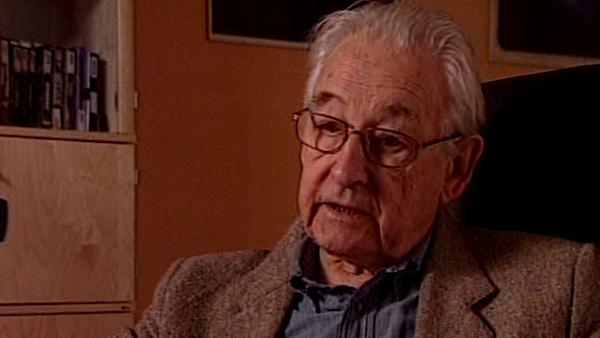

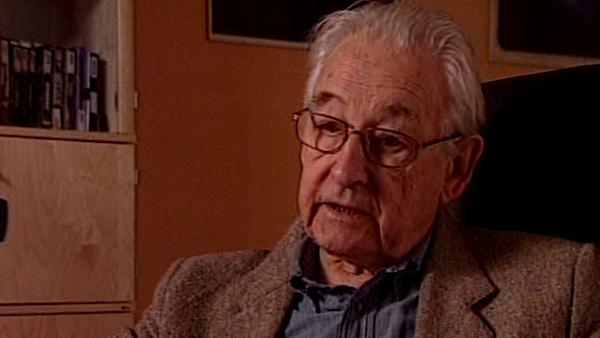

Polish film director Andrzej Wajda (1926-2016) was a towering presence in Polish cinema for six decades. His films, showing the horror of the German occupation of Poland, won awards at Cannes and established his reputation as both story-teller and commentator on Poland's turbulent history. As well as his impressive career in TV and film, he also served on the national Senate from 1989-91.

Title: The influence of Japanese theatre on "The Devils"

Listeners: Jacek Petrycki

Cinematographer Jacek Petrycki was born in Poznań, Poland in 1948. He has worked extensively in Poland and throughout the world. His credits include, for Agniezka Holland, Provincial Actors (1979), Europe, Europe (1990), Shot in the Heart (2001) and Julie Walking Home (2002), for Krysztof Kieslowski numerous short films including Camera Buff (1980) and No End (1985). Other credits include Journey to the Sun (1998), directed by Jesim Ustaoglu, which won the Golden Camera 300 award at the International Film Camera Festival, Shooters (2000) and The Valley (1999), both directed by Dan Reed, Unforgiving (1993) and Betrayed (1995) by Clive Gordon both of which won the BAFTA for best factual photography. Jacek Petrycki is also a teacher and a filmmaker.

Tags: The Devils, Japan, Osaka, Jagiellonian University, Bunraku, Kraków, Kabuki, Aleksiej Kiryłow, Iwan Szatow

Duration: 3 minutes, 57 seconds

Date story recorded: August 2003

Date story went live: 24 January 2008