NEXT STORY

My first operations

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

My first operations

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 11. Africa and the practise of medicine | 190 | 03:50 | |

| 12. My first operations | 169 | 01:18 | |

| 13. The battle of Ksar Ghilane | 231 | 03:48 | |

| 14. Meeting with a German soldier | 190 | 02:36 | |

| 15. Algiers and the death of the two brothers | 154 | 02:17 | |

| 16. The chaos of war | 140 | 01:04 | |

| 17. The landing in France | 134 | 01:57 | |

| 18. The injury that ended my career as a surgeon | 257 | 02:05 | |

| 19. Return to Paris | 153 | 01:54 | |

| 20. Reunited with my family | 1 | 203 | 01:13 |

Well, you know, for a start Africa... When you take a young Parisian student who has never left Paris, who's studying at the Medical Faculty, and that you take him and send him to black Africa, and in particular, that you leave him alone in a region as big as half of France to be that area's doctor, it's quite a change, it's rather surprising. It really was something very surprising. Because during that time I sometimes... At first I went to black Africa, I left with the Dakar expedition, where we were very badly welcomed, so we left again. Afterwards I went to Cameroon, then in the north, in Chad. And I was the doctor of a region which was more or less as big as half of France, with my two years of studying medicine. In other words, you couldn't ask me much. And it really was an extraordinary life... It was something completely new. And there, I learned a lot.

[Q] And did you have any problems with the Africans? Or did you not encounter any in the end? You were the doctor. Did you have very natural relationships? What I mean is that at the time you didn't feel any opposition?

No, at the time there weren't any. No, I was the doctor. So there was a village... I was the doctor for both the battalion infantry which had set up camp in the north, just north of the Chad lake, and at the same time for the region, meaning a village. Every morning I went to the village to do my visits. It was very picturesque. That was also something, coming from the 'Hopitaux de Paris', from the latest surgery techniques of the Saint-Antoine hospital and landing there where I was expected to run a small dispensary where women would come show me their troubles, and where I tried to spot the syphilitic cases because it was very important for the troops... It was a rather different job.

[Q] And for example did you have everything you needed in terms of medicine in order to help at least a little?

We mainly had... I remember that there was a captain doctor with an incredible accent from the South of France, whom I replaced. He was very happy to see me arrive because he'd been there six months, and he was fed up. He said to me, 'Can you imagine, that here, there are no white women!' So he was very happy to arrive and to leave. He explained to me what I should and shouldn't do: in the morning you do your... you treat the soldiers. Afterwards in the afternoon, you go to the dispensary and you treat the civilians. And on that note, he left, too happy! You really learned medicine on the job. I really didn't learn much about medicine. You know medicine, soldier medicine isn't real medicine. What's wrong with you? My head hurts, Lieutenant. Take an aspirin tablet. That was essentially it, medicine. When there was something more serious, we would send it to the hospital. But there, miles away from anything in Chad, you needed two days to get to the hospital in Fort Lamy.

Ben vous savez d'abord l'Afrique... Quand vous prenez un petit étudiant parisien qui n'a jamais quitté Paris, qui est à la faculté de médecine, et que vous le prenez et que vous le mettez en Afrique noire, et en particulier, que vous le mettez tout seul dans un territoire grand comme la moitié de la France pour être médecin de ce coin-là, ça change, ça étonne quand même. C'était quand même quelque chose de très surprenant. Parce que là, ça m'est arrivé pendant... J'ai été d'abord en Afrique noire, je suis partie avec l'expédition de Dakar où on a été mal reçu à Dakar, donc on est reparti. J'ai été ensuite au Cameroun, puis dans le nord, au Tchad. Et j'étais médecin d'un territoire qui était grand comme à peu près la moitié de la France, avec mes deux années de médecine. Autrement dit, il ne fallait pas trop m'en demander. Et là c'était quand même une vie extraor... C'était quelque chose de tout à fait nouveau. Et là j'ai appris beaucoup là.

[Q] Est-ce que, les africains, vous avez eu des problèmes, ou finalement, il n'y avait aucun problème, vous étiez le médecin? Vous avez eu des rapports très naturels? Je veux dire vous n'avez jamais senti, à l'époque, d'opposition?

Ah non, à cette époque-Là il n'y en avait pas du tout. Non j'étais médecin. Alors il y avait un village... J'étais médecin à la fois d'un bataillon d'infanterie qui était installé au nord, juste au nord du lac Tchad, et j'étais en même temps médecin de la région, c'est-à-dire d'un village. J'allais tous les matins faire ma visite au village. Ça c'était très pittoresque. Ça aussi c'était quelque chose, sortant des hôpitaux de Paris, des services de chirurgie dernier cri de l'hôpital Saint-Antoine et atterrissant pour faire fonctionner une espèce de petit machin sanitaire où les femmes venaient me montrer leurs difficultés, où je tâchais de repérer les syphilitiques parce que c'était important pour la troupe... C'était quand même un autre métier.

[Q] Et vous aviez ce qu'il fallait comme médicament par exemple pour pouvoir quand même aider un peu?

On avait essentiellement... Je me rappelle, il y avait un médecin capitaine avec un formidable accent du midi, que j'ai remplacé. Qui était très content de me voir arriver parce qu'il était là depuis six mois, qu'il en avait jusque-là. Il m'a dit, 'Tu ne te rends pas compte', ici, il n'y a pas de blanches, il n' y a pas de femmes blanches! Alors il était très content d'arriver et de s'en aller. Et il m'a expliqué ce qu'il fallait faire ou pas faire- Le matin, tu fais ton... tu soignes les militaires. Ensuite l'après-midi, tu vas au dispensaire et tu soignes les civils. Et là-dessus, il est parti, trop content!

[Q] Vous avez appris vraiment la médecine sur le tas.

Je n'ai vraiment pas appris beaucoup de médecine. Vous savez la médecine, la médecine de tirailleur, ce n'est pas de la vraie médecine. Qu'est-ce que tu as? Moi, y en a mal la tête mon lieutenant. Un comprimé d'aspirine. C'était essentiellement ça, la médecine. Quand il y avait quelque chose plus compliquée, on l' envoyait à l'hôpital. Mais l'hôpital dans ce coin perdu du Tchad, il fallait deux jours pour y aller à Fort Lami.

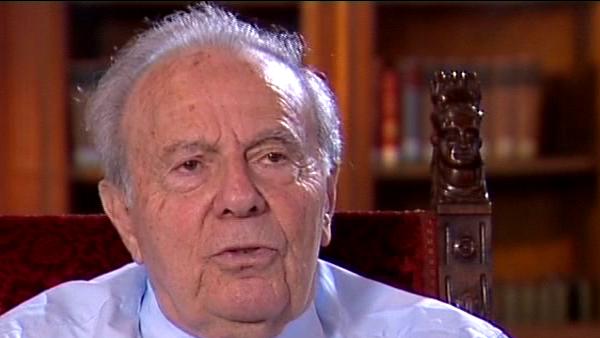

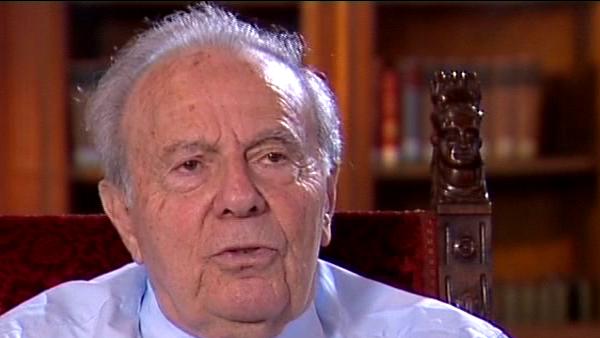

François Jacob (1920-2013) was a French biochemist whose work has led to advances in the understanding of the ways in which genes are controlled. In 1965 he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, together with Jacque Monod and André Lwoff, for his contribution to the field of biochemistry. His later work included studies on gene control and on embryogenesis. Besides the Nobel Prize, he also received the Lewis Thomas Prize for Writing about Science for 1996 and was elected a member of the French Academy in 1996.

Title: Africa and the practise of medicine

Listeners: Michel Morange

Michel Morange is a professor of Biology and Director of the Centre Cavaillès of History and Philosophy of Science at the Ecole Normale Supérieure. After having obtained a Bachelor in biochemistry and two PhDs, one in Biochemistry, the other in History and Philosophy of Science, he went on to join the research unit of Molecular Genetics headed by François Jacob, in the Department of Molecular Biology at the Pasteur Institute, Paris. Together with Olivier Bensaude, he discovered that Heat Shock Proteins are specifically expressed on the onset of the mouse zygotic genome activation. Since then he has been working on the properties of Heat Shock Proteins, their role in aggregation and on the regulation of expression of these proteins during mouse embryogenesis. He is the author of 'A History of Molecular Biology' and 'The Misunderstood Gene'.

Michel Morange est généticien et professeur à L'Université Paris VI ainsi qu'à l'Ecole Normale Supérieure où il dirige le Centre Cavaillès d'Histoire et de Philosophie des Sciences. Après l'obtention d'une license en Biochimie ainsi que de deux Doctorats, l'un en Biochimie, l'autre en Histoire et Philosophie des Sciences, il rejoint le laboratoire de Génétique Moléculaire dirigé par le Professeur François Jacob à l'Institut Pasteur. Ses principaux travaux de recherche se sont portés sur l'Histoire de la Biologie au XXème siècle, la naissance et le développement de la Biologie Moléculaire, ses transformations récentes et ses interactions avec les autres disciplines biologiques. Auteur de "La Part des Gènes" ainsi que de "Histoire de la Biologie Moléculaire", il est spécialiste de la structure, de la fonction et de l'ingénerie des protéines.

Tags: Africa, Dakar expedition, village, doctor, dispensary, medicine

Duration: 3 minutes, 51 seconds

Date story recorded: October 2004

Date story went live: 24 January 2008