NEXT STORY

Poetry readings: Beasts

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Poetry readings: Beasts

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 61. About Lying and the way poems happen | 492 | 04:01 | |

| 62. Poetry readings: Beasts | 715 | 02:32 | |

| 63. Introduction to Cottage Street, 1953 | 601 | 01:06 | |

| 64. Poetry reading: Cottage Street, 1953 | 451 | 04:09 | |

| 65. Introduction to Altitudes | 218 | 00:59 | |

| 66. Poetry readings: Altitudes | 240 | 02:03 | |

| 67. Introduction to A Christmas Hymn | 420 | 01:37 | |

| 68. Poetry readings: A Christmas Hymn | 844 | 02:29 | |

| 69. Buying property in Cummington inspires 'Fern-Beds in Hampshire... | 125 | 06:09 | |

| 70. Poetry readings: Seed Leaves | 324 | 03:00 |

This was published in the New Yorker Magazine at a time when Howard Moss, the usual editor at the time, was on vacation, and whoever was substituting for him called me and said, 'It's very nice, lively poem, I wonder if you could put a few clarifying lines in it toward the end?' And so I wrote the line, 'And to the dove that hatched the dovetailed world', and we stuck that in, and whether or not it was clarifying, I think I was talked into one of the better lines in the poem.

[Q] It was Charles McGrath by the way.

Oh, was it? Well, I think the poem probably does ultimately boil down to a rather simple statement, that all things are of one nature, that all metaphors are in some sense true.

I daresay as I was reading, that any hero would have heard when I shifted into Miltonic gear, began to talk about Satan's escape from hell and indeed quoted, 'In a black mist low creeping'. I think Milton happened in this poem partly because of his concerns of his great poem, Paradise Lost, and the relation of those concerns to what I am talking about, but also because Milton was the great master of supple discourse in the blank verse form. It came to me as I was beginning this poem that since it was going to be argumentative, since it was going to be full of instances, I did feel that in advance, that blank versed might be the form in which to do my talking.

That's the way poems happen with me. I have some sense of what I may be about to say or entertain. I have some sense of what words might be lively in the first or second line of the poem, and then the form of the poem simply evolves accordingly. That is to say what the poem is about to say is what gives shape to the poem. I generally know - I can't say why but I expect I'm not alone in this - I generally know when I start a poem about how long it's going to be, and I think I know whether it's going to have a series of stages in it, which a stanza pattern would accommodate. I think I generally know what the tone, what the mood, what the drama of it is going to be, and whether therefore I'm in need of rhyme to stress one kind of emotion or another. I think I've fairly well explained why Lying took the, took the shape it did, and I think actually that it's one of my best efforts in the, in the form of blank verse discourse.

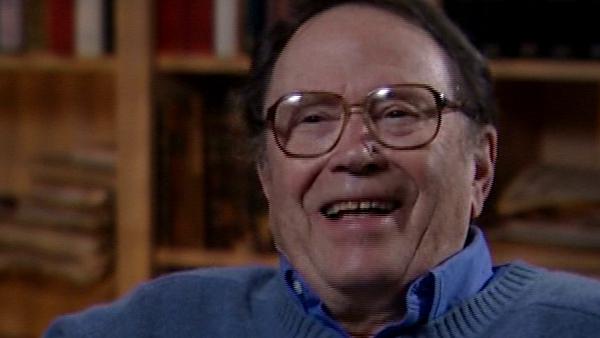

Acclaimed US poet Richard Wilbur (1921-2017) published many books and was twice awarded the Pulitzer Prize. He was less well known for creating a musical version of Voltaire's “Candide” with Bernstein and Hellman which is still produced throughout the world today.

Title: About "Lying" and the way poems happen

Listeners: David Sofield

David Sofield is the Samuel Williston Professor of English at Amherst College, where he has taught the reading and writing of poetry since 1965. He is the co-editor and a contributor to Under Criticism (1998) and the author of a book of poems, Light Disguise (2003).

Tags: New Yorker Magazine, Paradise Lost, John Milton

Duration: 4 minutes, 1 second

Date story recorded: April 2005

Date story went live: 29 September 2010