NEXT STORY

Encountering the wildlife of Burma

RELATED STORIES

NEXT STORY

Encountering the wildlife of Burma

RELATED STORIES

|

Views | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 21. Breakfast on the move | 39 | 02:06 | |

| 22. The doorway of Burma | 45 | 02:34 | |

| 23. The Royal Signals' lot in Burma | 54 | 03:22 | |

| 24. Encountering the wildlife of Burma | 43 | 04:27 | |

| 25. Elements of culture in the midst of war | 44 | 03:37 | |

| 26. The beginning of the end of the war | 53 | 02:39 | |

| 27. A dreary homecoming | 44 | 02:14 | |

| 28. The most terrifying day of my life | 100 | 04:50 | |

| 29. The biggest tree in the world | 1 | 52 | 05:02 |

| 30. Farewell to India | 1 | 59 | 03:23 |

What it was like in Burma – I would think action would be difficult… different from the true fighting to be in Signals because we had a little Dodge truck – everything was American, everything was American – a Dodge truck, okay. And that would carry us forward, and our job was to be really isolated between Division, on the one hand, and Brigade, on the other. And what we could do would be to communicate between one and the other.

And so, we learnt Morse code, and Morse code, you know, was another form of speech... do they still have Morse code? Probably not, probably not. But in those days, you learned Morse code and you could pick it up quickly, and you could send it quickly at 60 or even 80 words a minute, which was quite, quite fast. But I did get very fast at doing it and at sending it. And that was what we would do, mainly at night-time, but not only at night-time, but we would certainly work through the night.

And, yes, such was the routine. The days were divided into three. One of the days was supposedly a day off, the other day one worked morning and afternoon, and on the third day one worked all night. And these messages poured through from Brigade, and we relayed them on to Division.

And… for more than one time, we were actually attacked by wandering Japanese, a gang of Japanese. You see, at this stage, although our supply lines were terribly extended, just think of the Japanese supply lines. They were very, very bad indeed. And so these guys were starving and angry and they wanted to attack us – well, they wanted to kill us, but they also hoped they'd find some food. And so, we only had Lee Enfield rifles, the old rifle, the old rifle that the British had used in war after war. The Lee Enfield... God Almighty. And with that we could shoot the Japs when they tried to attack our little vehicle.

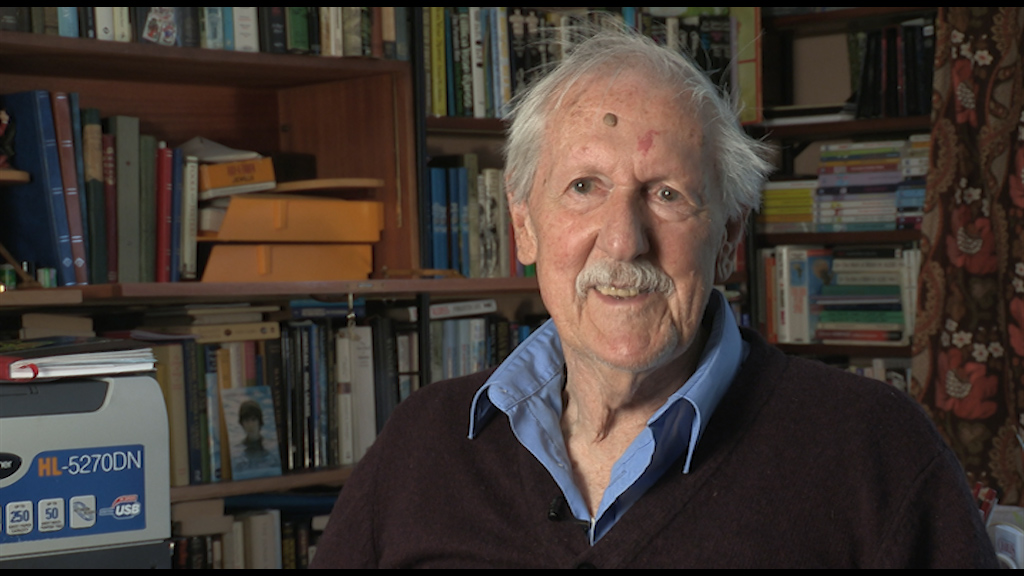

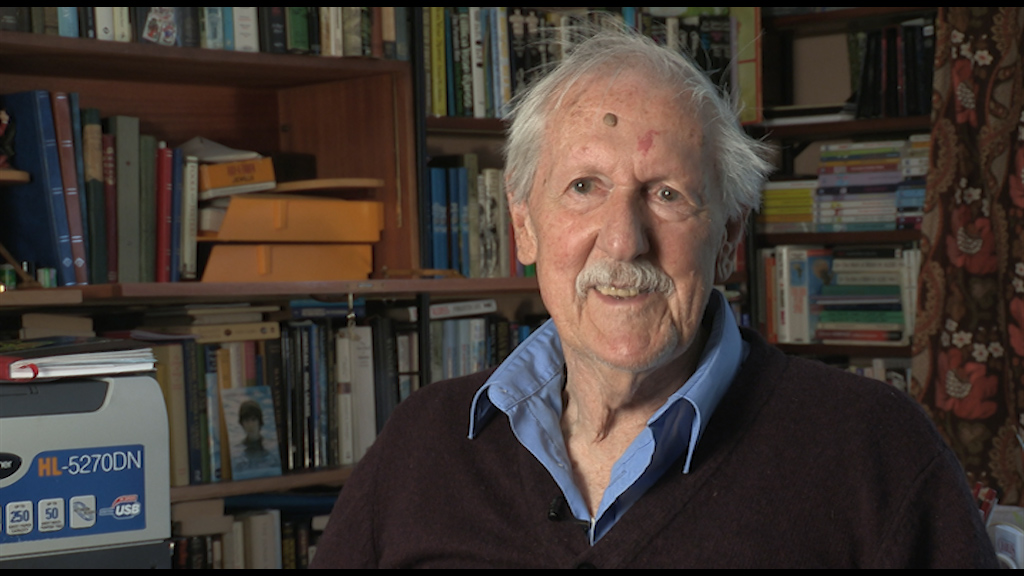

Brian Aldiss (1925-2017) was an English writer and anthologies editor, best known for his science fiction novels and short stories. He was educated at Framlingham College, Suffolk, and West Buckland School, Devon, and served in the Royal Signals between 1943-1947. After leaving the army, Aldiss worked as a bookseller in Oxford, an experience which provided the setting for his first book, 'The Brightfount Diaries' (1955). His first science fiction novel, 'Non-Stop', was published in 1958 while he was working as literary editor of the 'Oxford Mail'. His many prize-winning science fiction titles include 'Hothouse' (1962), which won the Hugo Award, 'The Saliva Tree' (1966), which was awarded the Nebula, and 'Helliconia Spring' (1982), which won both the British Science Fiction Association Award and the John W Campbell Memorial Award. Several of his books have been adapted for the cinema. His story, 'Supertoys Last All Summer Long', was adapted and released as the film 'AI' in 2001. His book 'Jocasta' (2005), is a reworking of Sophocles' classic Theban plays, 'Oedipus Rex' and 'Antigone'.

Title: The Royal Signals' lot in Burma

Listeners: Christopher Sykes

Christopher Sykes is an independent documentary producer who has made a number of films about science and scientists for BBC TV, Channel Four, and PBS.

Tags: Burma, Royal Signals

Duration: 3 minutes, 22 seconds

Date story recorded: September 2014

Date story went live: 17 August 2015